I used to be a music lawyer and I was a bit of an authority (for a while) on sampling and sample clearance in the early ‘90’s.

Then I ran a bunch of dance labels and worked with a lot of electronic artists.

I have cleared a lot of samples but I have released way more records with samples in them that we didn’t bother to clear.

Why?

Because we thought that no-one would notice that we’d used their music - these were generally small specialist underground records - and that if they did, we would be able to agree something after the event, if the need ever arose.

The reality is that it was too much bother and too expensive to try and clear a sample of an obscure and hard to find piece of music or of a snippet of a big successful tune when you knew that your record was going to sell just a few thousand copies - i.e. we felt at the time that the risk was well worth it. And hundreds of thousands of records have been released with uncleared samples in them.

Will I get sued for using a sample?

There are very, very few cases where someone who samples a record ends up in court - and there’s two reasons for that.

If your record containing an uncleared sample goes from being an underground momentary thing of interest to a limited audience to about to become a radio/commercial hit of any scale, you will quickly clear or remove/replace the offending sample(s). Well, you will, or the indie or major label that have come to sign your record will do it for you.

It’s when a record appears on everyone’s radar that it becomes time to clear it. At that point, if you don’t, you’re going to be in trouble. Remember the adage ‘“Where there’s a hit there’s a writ” - it is the absolute truth.

Secondly, if your record contains a sample and you didn’t clear it, you are infringing the original owner’s copyright - and they have you ‘bang to rights’. If they do discover your small scale release and if they care enough to contact you and point out your infringement, then in most cases they can see that going to court is pointless as you, the sampler, won’t have any money worth suing you for!

So, generally they approach the sampler and point this fact out and you work out a deal. Hence, court case avoided.

What is sample clearance?

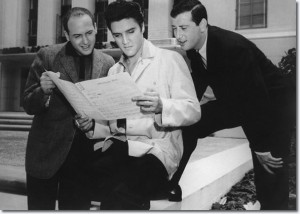

When you sample another person’s music you are reproducing two different copyrights - the recording itself but also the underlying musical work (the song - that part which a music publisher deals with, rather than a record label). Leiber & Stoller go over a song with Elvis Presley

Leiber & Stoller go over a song with Elvis Presley

For those that find that a difficult distinction, think of the days when all pop stars sang songs written by songwriters. Think Elvis and Leiber & Stoller.

Leiber & Stoller create the copyright which is the song - it can be written on sheet music before it is ever performed and recorded. Then, when it is performed by Elvis, he (or his record company) have created another different copyright in that recording of that performance. Every new and different recording is a new copyright.

Hopefully you can see that these two copyrights give rise to two income streams - one for the song and one for the recording.

Leiber & Stoller get paid for every radio or live performance of the song (whether that is a spin of the recording or Elvis singing live) and they get paid for every record made (that’s called a mechanical royalty and is paid by the record company - more on that another day as that get’s confusing!). Elvis only gets paid for every record made and sold - that’s the record royalty. (Just to confuse you some more, many countries, but not the US, do have an airplay royalty for the recording as well).

So when you sample a piece of that recording, you are also sampling the underlying song and you need to get the permission (or ‘clearance’) of all the owners of the copyright in the recording and the song. That means contacting the record company that owns the recording you have sampled but also all the songwriters and/or their music publishers.

Generally the record company will take a fee (perhaps tens of thousands of dollars) and a per unit royalty for every record sold and they may well impose limitations on the use. The songwriters and music publishers will usually take a percentage share in your new song that has sampled theirs. The amounts being down to negotiation.

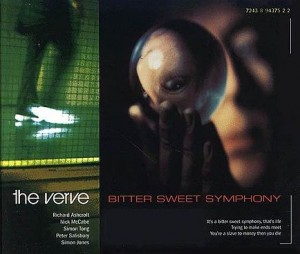

The thing is, they have you over a barrel. Bitter Sweet Symphony’ was one big sample Once you have sampled their work and told them, they can ask for whatever they want.

Bitter Sweet Symphony’ was one big sample Once you have sampled their work and told them, they can ask for whatever they want.

The Verve gave 100% of the song ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’ to Jagger and Richards as it sampled a version of one of their songs. Interestingly the recording that they sampled wasn’t the Stones, but an orchestral version by someone else. Read more about that case here.

Once you have the agreement of the copyright owners of the song and recording, you’re set.

This existence of two copyrights also explains the very common misconception amongst musicians that they do not need to worry about sample clearance if they ‘re-record’ a sample. True - if you re-record the sample that you lifted from someone else’s record, you don’t need to clear the recording, because you have made a new one and you own the copyright in that. But, your new recording still reproduces the underlying song and therefore still infringes that unless you clear it. Re-recording deals with half the issue, but don’t forget the other half.

How much is too much?

Usually, any little bit is too much.

In fact, the law and exactly how it is applied depends on where in the world you are. There are treaties between countries that aim to apply essentially the same copyright laws throughout the world but there are specific differences.

In very general terms you are infringing the rights of another person’s copyright if you ‘substantially reproduce’ their work. And the definition of what counts as being ‘substantial’ is usually not set out in a country’s relevant copyright law (the Acts or Statutes) but is based on interpretation by judges in cases that go to trial. Then future cases refer back to the decisions in prior trials - this is what is called ‘case law’.

However, since most cases don’t go to trial and get settled or negotiated long before a judge gets to deliberate, there are very few cases that a judge can refer to for guidance. Those few that have gone all the way in the UK and US have led lawyers to err very heavily on the side of caution and that is upheld by the way and the levels at which all involved negotiate clearances on a day to day basis.

In other words, the person being sampled whose permission you are seeking has all the cards.

If you have sampled a single recognisable note, this may well be seen to be ‘substantial’. If any reasonable person listening to your new record could tell that you have used a sample, then it is almost certainly a substantial use and legally requires clearing.

But you can take the drums only from a track and that’s fine, right? Err, no. Probably not.

If you have sampled a recording you fall at the first fence since you cannot deny that those drums (or whatever part you’ve taken) come from the other person’s recording. Given that admission, even the smallest section is probably enough to require permission. I can’t be sure, as it takes a final judgement in a court case to get the definitive view, but should you risk it?

In the real world, if you’re a small-time artist, you may well do just that. And I wouldn’t blame you.

As I said above, hundreds of thousands of records have been released without clearing samples and almost all ‘get away with it’ - particularly so if the release is small-scale and no significant money is made.

But, it is extremely important to note that if you get sued the amount of a claim by the person you have sampled, in most countries, need NOT be related to how much you made from releasing your infringing record.

The decision by a judge to award damages to the person you sampled is usually equated to the loss they have suffered rather than the money you made. And that loss can be based on anything that they can argue. Sure, often it does refer to the amount you made from releasing your infringing record, but not always.

The cautionary tale

So, this is where you get to see what happens when it all goes wong!

At the end of last week a Danish court case concluded that two musicians who had made a record in 2003 by using a sample had infringed the rights of a songwriter and a record company and ordered them to pay damages approaching $150,000 - way more than they ever made from the record.

This is enough to finish their careers and affect them for the rest of their lives. Read all about the Djuma Soundsystem case here. This case could be reversed on appeal and, depending on where you live, it is unlikely to be used as ‘case law’ in your country and therefore it won’t lead to a swathe of sampling cases against the little guy.

But it is a reminder that any one of the hundreds of thousands of records that have been released (or are going to be released in the future) with uncleared samples and which the artists think are going to be small scale successes, could lead to you being sued.

Should you worry? No, I don’t think you should, but you should be aware.

I think the Danish case is unlikely to be upheld and the guys were very unlucky that it didn’t get negotiated to a settlement that they could afford before going to trial. In almost all cases this would have been resolved before going to court.

And, of course, if your release is likely to be a commercial success, do deal with any sample issues before release. Success brings attention and people will then sue and they will push hard for a very stiff deal if you ignored their samples! Just remember that if you sample a record then the basic position is that you are infringing the rights of two sets of people and that could come back and bite you in the ass.

Sample clearance is the answer but we all know that in the real world that’s not always going to happen.

Hopefully, forewarned is forearmed!

This article originally appeared on our music marketing blog where we write on any topic that takes our fancy and where our experience may help DIY or indie musicians.

You can find us on Twitter where we pass on daily tips and also on Facebook.