Monday

Jun072010

June 7, 2010

June 7, 2010 Maverick Recording Company v. Whitney Harper

(Written by Phil Hill)

For the past month or so I have been working with Professor Charles Nesson of Harvard Law School in preparing a plea to the Supreme Court to hear the case of Whitney Harper, the “innocent infringer”. Our plea takes the form of a petition for certiorari to the United States Supreme Court, just recently filed by her lawyer, Kiwi Camara, and will take further shape in the expressions of support we can gather for it.

Whitney Harper is one of the 40,000+ targets of legal action the RIAA has brought against ordinary Americans in downloading music for free. Each one of these is a classic case of the little guy against giant multinational corporations. An army of lawyers with essentially limitless financial resources against individual defendants with pro bono lawyers.

These battles are fought in a legal system that cares little about what is just and appropriate for the Internet Era. All the while, legal precedent is being shaped that is unnerving for those who care about the future of music and the freedom of the internet.

Whitney Harper’s case is important, though it has yet to be noticed. If upheld, the decision essentially makes downloading of copyrighted material a strict liability offense when the plaintiffs only seek the statutory minimum of $750 per work. A recent study found that the average British teenager had 800 illegally downloaded songs on their iPod. This means that each teenager in the UK is liable for $600,000 on their iPod alone. If you spread that out over the 40,000 or so lawsuits already filed by the RIAA, that equates to roughly $24 BILLION.

As yet, the RIAA has only requested damages for a handful of songs in each case. However, the labels may be less generous if the judicial system supports their arguments. Furthermore, it would be bad policy to continually rely on a plaintiff’s beneficence to litigate only a small sample of the files they are entitled, especially when windfall judgments are all but guaranteed.

Moreover, if it goes unreviewed this case provides a key step in the legal logic that will be used to justify ISPs terminating users’ net connections for violating copyrights. It would effectively disallow defense of any kind based on innocence.

Ireland has become the first country to implement very aggressive “internet filtering” policies. Under this scheme, Eircom—the largest ISP in Ireland—receives a list of IP addresses from IRMA, the Irish Recorded Music Association. Infringers are sent warnings through their ISP and after three strikes their internet service is shut off. Obama is prepared to put the frame work in place without consulting the House or Senate.

A leaked draft of the ACTA convention contemplates criminal liability for inciting copyright violation (prison as well as fines), creates oversight panels, and contemplates institutionalized surveillance of data traffic across the internet to enforce these policies.

The Background

Whitney Harper was 16 at the time of her infringement and understood KaZaA and other filesharing programs to be akin to listening on a legitimate internet radio station. In fact, at the time KaZaA claimed to be “100% legal” on its site. She had no intent to possess the music, let alone share or distribute it. The district courts decided that there was a genuine issue as to the character of her infringement and allowed her to press what is known as the “innocent infringer defense”. This allows the courts to reduce the statutory minimums from $750 per infringed work to $200.

The labels fought this by arguing that notices appeared on the legitimate CDs available at record stores. According to copyright law, when a notice appears “on the phonorecord or phonorecords to which a defendant…had access” no weight shall be given to an innocent infringer defense. The district court found this reasoning to be lacking since the media involved were mp3 files without copyright notices on them and the CDs themselves were never in the equation.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit reversed that aspect of the decision and the minimums were raised to $750 and made automatic in the sense of eliminating any need for a jury trial. They found that notice on CDs, which the defendant never saw, may not have known existed, and was too young and untutored to appreciate were sufficient to foreclose the innocent infringer defense as a matter of law. As such, the qualities of a defendant—age, education, understanding of the situation, cognitive abilities, etc—have no bearing on the application of law and assessment of damages on the basis of the industry’s internet investigation.

Why this is a Terrible Decision

Many of the relevant sections of the copyright laws were written before many of us had computers in our homes and before the spread of the internet. This was during the transition from analog to digital and no one writing the laws or otherwise foresaw the ability of exponential duplication. At the time, there was no way to duplicate music without having a physical object in front of you. Under these circumstances no leniency need be granted to a sentient person who willfully chooses to ignore a warning in their hands, in front of their face that says “HEY STUPID DON’T COPY ME!!”

The appellate Harper decision extends that notion unreasonably far by taking the notice out that person’s hands, out of their home, and putting it across town or maybe even in another town altogether. Under the Harper decision, everyone is beholden to a warning that they may not understand, may not know to look for, located on an object that they may not know exists, located in a store that they may never go to. All based on some metaphysical possibility that there is “access” to copyright notice somewhere out there in the ether.

Copyright is not generally addressed in an academic setting until college. Furthermore, there is the very real possibility that the youth of today has never and will never hold a physical CD or set foot in a real record store. As such, it seems that an individual’s mindset and experience should have a very real bearing on the outcome of these cases. Not according to the Fifth Circuit—as long as CDs have notice on them, whether you’ve seen them or not, whether you are old enough to read or mentally capable enough to understand, you are responsible for the strictures of copyright.

But not every CD sold at a record store contains copyright notice. Just a cursory glance at my personal collection reveals a shocking number of very high profile records without any copyright notice on the outer container: Antony and the Johnsons Crying Light, Arcade Fire Funeral and Neon Bible, Deathcab for Cutie You Can Play These Songs with Chords, The Decemberists Castaways and Cutouts, Sunny Day Real Estate Diary, Wilco Yankee Hotel Foxtrot.

Even the district court agreed that some CDs or even the majority of CDs possessing copyright notices on them does little to establish that downloading is illegal. The court also found that there was a genuine question as to whether or not Harper would have or should have known that such notices were applicable in the situation as she understood it. The appellate court disagreed.

The Importance of this Case

If the appellate decision holds up, it means that no further information can be or needs to be taken into account in a filesharing case. It will affirm the sufficiency of “access” as defined in the Fifth Circuit. This essentially becomes a legal shortcut to acquiring damages. All a label needs is a private investigatory body like MediaSentry to supply their lawyers with a list of filesharers to sue. If defendants can’t dispute ownership of the files, then that is all the courts need to file summary judgment, without hearing any arguments, without going before a jury.

Ultimately that is what the labels and copyright industry want—fewer questions and fewer nuances. Many of these cases request only the statutory minimums. The reason is that if the labels do not ask for anything above that, then there can be no legal question as to the severity of damage done by filesharers. There can be no questions of constitutionality, exorbitance, injustice, or impropriety. If this decision stands, then filesharing cases will become a streamlined, disinterested, purely mechanical process.

Why You Should Care

Many artists, including Jason Mraz, Steve Winwood, and Heart, have said that they support filesharing. Others such as Adam Duritz, Annie Lennox, Chuck D, Peter Gabriel, David Gray, Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason, and The Clash’s Mick Jones have indicated that they do not believe the public should be prosecuted for downloads.

Whatever your views are, you do not need to condone filesharing in this case. Innocent infringement does not absolve liability. It is still an admission of guilt, but it allows a decrease in the statutory minimums if mitigating circumstances are allowed to be heard and deemed to be germane. Defendants are still forced to pay a minimum of $200/song, which many would agree is sufficient in any case of filesharing if not still exorbitant. But most importantly, allowing a defendant to press innocent infringement affords them the opportunity be heard by a jury rather than fall victim to an automatic process that controls the outcome of the case, the damages, and maybe their internet connection.

This petition does not attempt to question the legality of filesharing, nor does it attempt to call into question the fairness of the laws. All it asks is for the preservation of an enclave for innocence.

Artists should not condone their labels using their music to litigate against and alienate their audience. Do not give them a free pass to fleece your fans. If you believe that filesharing could be a useful tool in connecting with your audience, the Harper decision creates a world where your fans would be and should be afraid to download anything you put out on your site, on P2P, or anywhere else on the net. If you support a free internet, you should not condone a legal precedent which allows something you’ve never seen at some non-uniform location out there in the universe to hold you responsible for actions that violate its orders. The consequences are apparent in Ireland and could very well become apparent here in the states in the near future.

But in the interest of the case at hand, as a society we should not condone a world that throws the book at someone who knows not what they do, who intends no harm in their actions, and whose accuser makes no specific claims of intentional or inadvertent harm. Our legal system should not be used to play Gotcha with unwitting citizens and entitle their tormentors to unjust, bankrupting windfalls.

The petition: http://joelfightsback.com/wp-content/uploads/harper-petition-for-cert.pdf

Originally posted here: http://blog.fixyourmix.com/2010/maverick-recording-company-v-whitney-harper/

Phil Hill has had a remarkable career as an audio engineer and producer in music, film, and television. In addition to his award-winning work, he is currently focusing his efforts on the pressing legal issues that confront the entertainment industry in the Digital Era. For a generation of consumers who may never hold a physical record or set foot in a real record store, the laws of yesteryear must be rethought. In working with Harvard Law School, he endeavors to create a vibrant musical economy that embraces the Internet and innovative technologies. He can be contacted at phil@fixyourmix.com

For the past month or so I have been working with Professor Charles Nesson of Harvard Law School in preparing a plea to the Supreme Court to hear the case of Whitney Harper, the “innocent infringer”. Our plea takes the form of a petition for certiorari to the United States Supreme Court, just recently filed by her lawyer, Kiwi Camara, and will take further shape in the expressions of support we can gather for it.

Whitney Harper is one of the 40,000+ targets of legal action the RIAA has brought against ordinary Americans in downloading music for free. Each one of these is a classic case of the little guy against giant multinational corporations. An army of lawyers with essentially limitless financial resources against individual defendants with pro bono lawyers.

These battles are fought in a legal system that cares little about what is just and appropriate for the Internet Era. All the while, legal precedent is being shaped that is unnerving for those who care about the future of music and the freedom of the internet.

Whitney Harper’s case is important, though it has yet to be noticed. If upheld, the decision essentially makes downloading of copyrighted material a strict liability offense when the plaintiffs only seek the statutory minimum of $750 per work. A recent study found that the average British teenager had 800 illegally downloaded songs on their iPod. This means that each teenager in the UK is liable for $600,000 on their iPod alone. If you spread that out over the 40,000 or so lawsuits already filed by the RIAA, that equates to roughly $24 BILLION.

As yet, the RIAA has only requested damages for a handful of songs in each case. However, the labels may be less generous if the judicial system supports their arguments. Furthermore, it would be bad policy to continually rely on a plaintiff’s beneficence to litigate only a small sample of the files they are entitled, especially when windfall judgments are all but guaranteed.

Moreover, if it goes unreviewed this case provides a key step in the legal logic that will be used to justify ISPs terminating users’ net connections for violating copyrights. It would effectively disallow defense of any kind based on innocence.

Ireland has become the first country to implement very aggressive “internet filtering” policies. Under this scheme, Eircom—the largest ISP in Ireland—receives a list of IP addresses from IRMA, the Irish Recorded Music Association. Infringers are sent warnings through their ISP and after three strikes their internet service is shut off. Obama is prepared to put the frame work in place without consulting the House or Senate.

A leaked draft of the ACTA convention contemplates criminal liability for inciting copyright violation (prison as well as fines), creates oversight panels, and contemplates institutionalized surveillance of data traffic across the internet to enforce these policies.

The Background

Whitney Harper was 16 at the time of her infringement and understood KaZaA and other filesharing programs to be akin to listening on a legitimate internet radio station. In fact, at the time KaZaA claimed to be “100% legal” on its site. She had no intent to possess the music, let alone share or distribute it. The district courts decided that there was a genuine issue as to the character of her infringement and allowed her to press what is known as the “innocent infringer defense”. This allows the courts to reduce the statutory minimums from $750 per infringed work to $200.

The labels fought this by arguing that notices appeared on the legitimate CDs available at record stores. According to copyright law, when a notice appears “on the phonorecord or phonorecords to which a defendant…had access” no weight shall be given to an innocent infringer defense. The district court found this reasoning to be lacking since the media involved were mp3 files without copyright notices on them and the CDs themselves were never in the equation.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit reversed that aspect of the decision and the minimums were raised to $750 and made automatic in the sense of eliminating any need for a jury trial. They found that notice on CDs, which the defendant never saw, may not have known existed, and was too young and untutored to appreciate were sufficient to foreclose the innocent infringer defense as a matter of law. As such, the qualities of a defendant—age, education, understanding of the situation, cognitive abilities, etc—have no bearing on the application of law and assessment of damages on the basis of the industry’s internet investigation.

Why this is a Terrible Decision

Many of the relevant sections of the copyright laws were written before many of us had computers in our homes and before the spread of the internet. This was during the transition from analog to digital and no one writing the laws or otherwise foresaw the ability of exponential duplication. At the time, there was no way to duplicate music without having a physical object in front of you. Under these circumstances no leniency need be granted to a sentient person who willfully chooses to ignore a warning in their hands, in front of their face that says “HEY STUPID DON’T COPY ME!!”

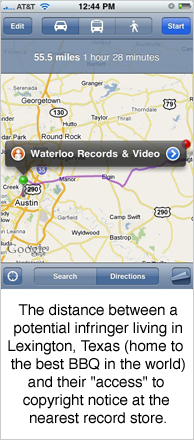

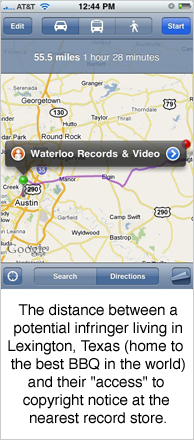

The appellate Harper decision extends that notion unreasonably far by taking the notice out that person’s hands, out of their home, and putting it across town or maybe even in another town altogether. Under the Harper decision, everyone is beholden to a warning that they may not understand, may not know to look for, located on an object that they may not know exists, located in a store that they may never go to. All based on some metaphysical possibility that there is “access” to copyright notice somewhere out there in the ether.

Copyright is not generally addressed in an academic setting until college. Furthermore, there is the very real possibility that the youth of today has never and will never hold a physical CD or set foot in a real record store. As such, it seems that an individual’s mindset and experience should have a very real bearing on the outcome of these cases. Not according to the Fifth Circuit—as long as CDs have notice on them, whether you’ve seen them or not, whether you are old enough to read or mentally capable enough to understand, you are responsible for the strictures of copyright.

But not every CD sold at a record store contains copyright notice. Just a cursory glance at my personal collection reveals a shocking number of very high profile records without any copyright notice on the outer container: Antony and the Johnsons Crying Light, Arcade Fire Funeral and Neon Bible, Deathcab for Cutie You Can Play These Songs with Chords, The Decemberists Castaways and Cutouts, Sunny Day Real Estate Diary, Wilco Yankee Hotel Foxtrot.

Even the district court agreed that some CDs or even the majority of CDs possessing copyright notices on them does little to establish that downloading is illegal. The court also found that there was a genuine question as to whether or not Harper would have or should have known that such notices were applicable in the situation as she understood it. The appellate court disagreed.

The Importance of this Case

If the appellate decision holds up, it means that no further information can be or needs to be taken into account in a filesharing case. It will affirm the sufficiency of “access” as defined in the Fifth Circuit. This essentially becomes a legal shortcut to acquiring damages. All a label needs is a private investigatory body like MediaSentry to supply their lawyers with a list of filesharers to sue. If defendants can’t dispute ownership of the files, then that is all the courts need to file summary judgment, without hearing any arguments, without going before a jury.

Ultimately that is what the labels and copyright industry want—fewer questions and fewer nuances. Many of these cases request only the statutory minimums. The reason is that if the labels do not ask for anything above that, then there can be no legal question as to the severity of damage done by filesharers. There can be no questions of constitutionality, exorbitance, injustice, or impropriety. If this decision stands, then filesharing cases will become a streamlined, disinterested, purely mechanical process.

Why You Should Care

Many artists, including Jason Mraz, Steve Winwood, and Heart, have said that they support filesharing. Others such as Adam Duritz, Annie Lennox, Chuck D, Peter Gabriel, David Gray, Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason, and The Clash’s Mick Jones have indicated that they do not believe the public should be prosecuted for downloads.

Whatever your views are, you do not need to condone filesharing in this case. Innocent infringement does not absolve liability. It is still an admission of guilt, but it allows a decrease in the statutory minimums if mitigating circumstances are allowed to be heard and deemed to be germane. Defendants are still forced to pay a minimum of $200/song, which many would agree is sufficient in any case of filesharing if not still exorbitant. But most importantly, allowing a defendant to press innocent infringement affords them the opportunity be heard by a jury rather than fall victim to an automatic process that controls the outcome of the case, the damages, and maybe their internet connection.

This petition does not attempt to question the legality of filesharing, nor does it attempt to call into question the fairness of the laws. All it asks is for the preservation of an enclave for innocence.

Artists should not condone their labels using their music to litigate against and alienate their audience. Do not give them a free pass to fleece your fans. If you believe that filesharing could be a useful tool in connecting with your audience, the Harper decision creates a world where your fans would be and should be afraid to download anything you put out on your site, on P2P, or anywhere else on the net. If you support a free internet, you should not condone a legal precedent which allows something you’ve never seen at some non-uniform location out there in the universe to hold you responsible for actions that violate its orders. The consequences are apparent in Ireland and could very well become apparent here in the states in the near future.

But in the interest of the case at hand, as a society we should not condone a world that throws the book at someone who knows not what they do, who intends no harm in their actions, and whose accuser makes no specific claims of intentional or inadvertent harm. Our legal system should not be used to play Gotcha with unwitting citizens and entitle their tormentors to unjust, bankrupting windfalls.

The petition: http://joelfightsback.com/wp-content/uploads/harper-petition-for-cert.pdf

Originally posted here: http://blog.fixyourmix.com/2010/maverick-recording-company-v-whitney-harper/

Phil Hill has had a remarkable career as an audio engineer and producer in music, film, and television. In addition to his award-winning work, he is currently focusing his efforts on the pressing legal issues that confront the entertainment industry in the Digital Era. For a generation of consumers who may never hold a physical record or set foot in a real record store, the laws of yesteryear must be rethought. In working with Harvard Law School, he endeavors to create a vibrant musical economy that embraces the Internet and innovative technologies. He can be contacted at phil@fixyourmix.com

Reader Comments (23)

Thanks for this...a great read and a f'ing disturbing problem.

What blows my mind is how utterly ineffective these cases are as deterrents to the actual crime. No matter how absurdly huge the final judgements are, cases like this remain roughly on par with being hit by lightning as far as the general public seems to be concerned. Nobody I know has changed their criminal ways one iota as a result of these nightmare lawsuits.

They're only succeeding in making their own public image worse, and destroying the lives of random Americans with absolutely no ability to pay. How these RIAA wonks can live with themselves is beyond me.

Hilary Rosen is working for BP now, so apparently being a sociopath is a key qualification.

think about all those "pay up or else" letters for hurt locker where they say that resistance is futile and all that. if this goes through it really will be!

I find it interesting that more artists haven't come out to say that file sharing is all right with them. Whatever happened to artists that would say,"I don't care about the money. I just want my music heard."? I long for a day when it's not about the money. Prove me right musicians!

My music is available for free and I'm happy for it to be shared BUT if an artist wasn't happy for their music to be shared, should they or ther record company not have the right to pursue any perceived wrong-doers?

I agree that this case is harsh but not knowing that something is illegal is not a defence.

@BM: I don't think there is any question that copyright holders should be able to protect their work. The question is if the way the RIAA is going about it is an abuse of the legal system. What we have are statutory penalties over 700 times the actual damages, a ratio far out of the bounds of constitutionality. Also, the limitless aggregation of minimum penalties is one of landmark

concern, though not available in this case due to civil procedure.

The main question in this case is whether innocent infringement, which reduces statutory minimums from $750 to $200 is available in this situation. Innocent infringement provides thar among other things, ignorance IS a defense in certain instances. Keep in mind that it is NOT an innocent plea. It is a guilty plea that still makes you liable. It just allows the minimums to be lowered in the judgment against you.

The code states that innocent infringement is unavailable when proper copyright notice appears "on the phonorecord...to which the defendant had access." So the question becomes whether notice on CDs (some CDs, not all) at a record store (which doesn't necessarily keep every CD on earth I'm stock) suffices as access to put a teenager on notice who has no idea what she is doing or if that notice would be applicable had she seen it.

The RIAA is creating a legal framework based on hypothetical conjecture that will guarantee them a minimum of $750 per song in every instance of downloading, with no cap on the total amount. More importantly, the precedent would foreclose the ability to raise questions on the quality of infringement or the situation or the defendant in future cases so long as plaintiff's only request the minimum.

I don't think anyone wants to prevent artists from exercising their copyrights, but this strategy is clearly an abuse that sets the stage for more abuse in the future. All the while, it erodes goodwill toward the music business and scares consumers as well as innovators from exploring new technologies.

I also want to add that in the deposition it was undisputed that KaZaA purported to be a 100% legitimate service at the time. By ignoring this aspect, the courts effectively allow traps where copyright holders could offer their stuff for free on "legitimate" sites and then sue anybody who downloads it. $750 bucks per schmuck who downloads wouldn't be a bad margin...

The one question I would have is how do websites become legitimate? The problem seems to be that there are so many you wouldn't generally question what was going on. For example how would LastFM be a legitimate site?

I guess this is akin to unwittingley buying stolen goods and then being given a jail sentance.

If I'm way off, then I suppose it shows the general ignorance of most of us consumers to how the law can be apllied.

I do not agree with the way the RIAA is going about this problem, however I do not agree with Mona's viewpoint whatsoever.Why should music be free? I can tell you that it costs $50,000 minimum to produce a real album for a band in a professional studio, (not a home pro tools studio) it costs any label $100,000 or more to market a new release , it costs$20,000 minimum to shoot a professional video and these are very conservative prices...Despite the plethora of cheap recordings and home studios around today real records cost a lot of money to make, so why should they be free? You can't walk into a shop and walk out with an ice cream for free, you can't drive a car out of a Ford lot for free, why should music be fore free? name any business that does what it does for FREE...musicians will often play for nothing because of their passion to play, but let's not forget it is a business and it cost a lot of time and money. Go to a music shop and buy a new Fender guitar and amplifier, after you have parted with the $3000 you will have experienced your first in a long line of expenses that are associated with being a musician. Music should not be free and we should not expect it to be.

There is no sustainable argument for stealing music files or any intellectual property for that matter just because it can be accessed digitally without the owners consent. It is unfortunate that children are being so aggressively targeted by the RIAA but the question you have to ask is why there isn't more basic home grown guidance in these matters (unless of course mom and dad are also uploading and downloading music files they did not purchase). Innovation is a good thing and It is the centerpiece of the argument for a free and unregulated internet. Innovation however challenges the societal order maintained by laws and regulations created by governments and backed by it's people to protect the innovator AND manage the details of copyright protection. Governments are not good at keeping up with innovation. We see in gross copyright infringement and also in the recent financial crisis whereby new "innovative" derivatives where left to proliferate in spite of their toxic potential. In a perfect world simple morality would step in and reduce the need for government intervention. Innovation has and will continue to challenged our morality. We should be ashamed of ourselves if we do not a least make a stand with our children on illegal downloading or worse if we are doing it ourselves.

the idea that musicians should be performing or creating recordings for free is ridiculous. unless we're going to start supporting musicians by giving them free rent, free groceries, free insurance, free equipment, free transportation, free college educations for their kids, and give them everything else they want for free, then we have no right to expect them to do what they do for nothing. besides, what kind of musical culture would we have if all music had to be developed as a hobby by part timers?

also, at 16 you're old enough to know that you can't take things without paying for them. a copyright notice doesn't have anything to do with it. perhaps they should make the penalty a loss of priveleges to use the internet. or maybe bar infringers from using a computer other than in a public library for 10 years. no cell phones, no laptops, no ipods, no video games - if a person can't handle the technology without infringing other people's rights, then why not take it away from them until they can prove they can follow simple rules of everyday life.

i don't think the monetary damages work in these instances and it's wrong to pass the penalties on to the parents. but this whole idea of playing innocent isn't fooling anyone. take away the priveleges and we'll even save parents money!

The argument about distance to a record store really turned me off. Because I bet there is a Target, Walmart, Best Buy, or Kmart in Lexington,TX. Granted I haven't heard much on this particular case as of yet, but I know a lot of the cases the RIAA has offered to settle out of court for amounts of around $4000 & only pursue the higher amounts when someone denies that what they were/are doing was/is illegal & thinks the court will agree with them. If that is the case here, then I personally think it's all fine & fair. If you want to say, "She was only 16!" Fine, then let her parents be responsible for the damages; more parents should take that responsibility for their children doing all sorts of illegal things anyway.

I fear that the comments have gotten just a bit off topic, but that happens in these forums. I'd like to try and steer it back to the case at hand.

First, I'd like to caution the audience against committing the same fallacy the RIAA has done with each of these cases which is forcing each of these individual defendants to stand and be punished for the actions of collective millions. Her personal infringements are a definitely a matter of debate, but her individual case should be viewed on it's individual facts, not the aggregate wrongs of millions of downloaders. Moreover, the reasoning behind this decision allows plaintiffs to foreclose individual arguments and make infingement a cold, disinterested application of mechanical laws. This does not comport with justice.

Second, I don't believe that Mona was saying that all music should be free. I think that she was merely voicing a concern that many music fans have: that the music industry is abusing the law to ring money out of unwitting consumers. This is an understandable concern simply because of the size of the awards against the questionable targets of litigation.

For artists and businesses who wish to explore new technologies to connect with their audience at a personal or commercial level, bankrupting decisions like this do a good job of destroying goodwill toward musicians as well as the business.

All of these comments raise great concerns and I'd like to respond to each. Afterward, I think I'll post a followup addressing a lot of the questions with more detail. I'm very glad that there is passion on this issue on both sides.

@Stan: I am glad to see that even though you have strong feelings about the value of music that you can concede that the way the RIAA has gone about this is wrong on a visceral level. While as a professional engineer I can say that I have made MANY professional albums with Top 10 artists at professional artists for MUCH less than 50k. That said, the amount of money an artist spends on their work is their prerogative. I'd also like to add that most major label marketing efforts are ineffectual and are generally directed toward the top 20% of artists who benefit the least from major marketing efforts. But that is an argument for another day.

The main issue is the strained metaphor of physical theft against downloading. Let me preface this by saying that even Whitney believes that she was wrong to have downloaded, even though she didn't know that she was downloading (she thought she was listening on an Internet Radio station). So we can go ahead and agree that in this case, all parties agree that filesharing is wrong, she is only seeking a modicum of leniency and consideration for her understanding of the situation.

That said, there is a distinct difference between downloading music and stealing a CD. At a record store, there are alarm systems and employees and devices and many things that indicate to everybody at every level that "hey, you gotta pay for that." The problem is that downloading music isn't like going to a record store. It'd be more like somebody coming to your house with a stack of CDs saying "take these, they're free". In fact, when Whitney used KaZaA, the site claimed that it was 100% legal. So it'd be like somebody coming to your house with a stack of CDs saying "Take these and it is 100% legal."

Lastly, at a record store, when you take the CD, that physical object is obviously no longer there, you know immediately that you have gotten something for nothing and it is wrong. With downloading, that original object never leaves. So to continue MY strained metaphor, it'd be like somebody coming into your house with a stack of CDs saying "take these it's 100% legal" and then after you take them, he still has them.

This is obviously strained, but to couch it in terms a teenager might actually experience, if their friend came over and offered to le them burn a few CDs, I don't think many of us would have a problem with that, yet it is equally illegal and subject to statutory minimums.

All this is to say that they are not exactly parallel situations. In one instance, there are many palpable indications of wrongdoing, but the other case seems to be notable devoid of indicators. Perhaps you disagree with a 16 year old, but what about a 4 year old? To this decision, it males no difference. But I think it does to anybody outside the legal system.

@Rick Riccobono: I am extremely glad to have your input on this matter and it is an honor to have you post. I agree 100% that morality should play an important role in informing these actions. Parents do play an important role in policing the actions of their children, but what is the cost of a lapse in their parenting? Is it $600,000? Those who have kids surely know that you cannot see EVERYTHING your children do, and there are many things that they are very good at hiding.

But more importantly, I want to pick your brain as an innovator in this digital age. How do you feel about a decision such as this that would guarantee AT LEAST the minimum statutory damages for each instance of potentially thousands. I know that you played a pivotal role in QTracks, a legitimate filesharing service. What do you think the effect would be on your business if someone had a very similar one, let's call it ZTracks that, like KaZaA in Whitney's case, claimed to be 100% legal. Then imagine that somebody using that service was slapped with $600,000 in fines despite relying on that disclaimer of legality. Do you think that would have a negative effect on the credibility of your service?

According to Harper's decision, the purported legitimacy of a site offering infringing music is a non-issue. The only thing that matters is that somebody else owns the rights and that you downloaded. Furthermore, there these CDs at the CD store that you could have checked against.

But I think that there is a logical extent to which we can expect anyone to verify legality. A site that claims to be legal would, for most, seem to offer a level of protection so that you could say "Hey, it was the site, not me!" But the Fifth Circuit disagrees.

Mr. Riccobono, this is not the optimum forum to have the most productive discussion of these matters, but I would sincerely love to exchange some ideas with you. If you are game, please drop me a line at phil [at] fixyourmix [dot] com.

@Mike: I adressed most of this with Stan, but I want to reiterate that I don't think anybody wants musicians to work for free. In fact, my sole concern is that we create a vibrant musical economy that supports working class musicians as well as megastars. Unfortunately, we are living a bifurcated reality wheyouths vast majority of musicians are either making millions or working for free. One of the best ways to lose your market us to sue your consumers into bankruptcy. And moreso than losing your own fans, the actions of an "industry trade group" unfairly holds other musicians not seeking exorbitant legal actions responsible in the minds of downloaders damaging the market for all musicians.

Your ideas are intriguing though because clearly even these exorbitant awards don't seem to curb downloading. Maybe it was just the movie Hackers, but I seem to recall that when hacking was a major legal concern that courts enjoined offenders from going near computers etc. for a period of time. It is an interesting thought to have courts impose that penalty, although I question the justice in doing that against a minor who will enter college being unable to participate in school with often requisite technology. Let alone function in the workplace.

Ireland has instituted a 3 Strikes You're Out policy whereby they receive a list of names from IRMA, the Irish Recorded Music Assiciation, and after three offenses service is cutoff. Thus raises concerns about private industry monitoring computer use and suspending your Internet access in the Internet Era. Plus we all know that 3 infringements over 1 IP address doesn't mean one person infringing 3 times. That raises concerns about punishing a family of four for infractions of one or two.

I believe these issues are making their way to the US via the ACTA convention. This case would allow all this to take place by making filesharing a clearcut, mechanical offense. I hope to establish that there is a deserving bit of nuance.

@Mike: Lexington is an interesting selection because it is a town that is very secluded, yet heavily travelled because of Snow's BBQ. Snow's us a store that is open one day a week from 9 am until they run out, usually about noon. Imagine a town that you have to drive sn hour and a half to via back roads that consists of four roads and would sustain a business with such a strange model. That is Lexington--a place with Internet, but no Walmart.

The nearest Target is actually in Austin, also about an hour and a half away. Walmart us about 30 minutes away. The point is merely made to ask ourselves how reasonably far should we require someone to go to verify copyright? Especially when something is on the screen in your patents' kitchen telling you to download and that doing so is 100% free and legal.

But more importantly, I think your point makes an interesting suggestion. You see, the courts indicated in BMG v Gonzalez that one could go to a "local record store" to verify copyright. That is why I chose Waterloo, the most "local" record store to someone in Lexington. Of course there us no guarantee that the CD us in stock there since it simply isn't possible for any store to have every record on Earth, so the courts reasoning is purely speculative.

But suggesting that one go to Walmart takes it a bit further. You see, I know in my mind that Walmart has CDs, but I also know that the CDs they carry are CDs I don't want. As such, the first place I think of to check for CDs if I needed to verify something is not Walmart, yet I would be beholden to Walmart's hypothetical inventory.

I think this highlights the troubling requirements of verifying copyright at non-standard commercial locations.

Another question is, if I go to Walmart, Target, Waterloo, Virgin, etc. If I drive around for three hours and can't find the record I'm after, does that mean I have put forth a good faith effort and should be allowed to download? I don't think so. But there is this gray area in the BMG reasoning that would seem to indicate that it is so.

One last comment that I'd like to hear thoughts on: my friend recently released his EP, a product of many years of effort at significant financial cost to himself. He made the tracks available for download and in the first day he had 2000 people listening.

As a fun experiment, I did the calculations and found that if he sued all those listeners for downloading his songs for the statutory minimum, (bearing in mind that claims of legitimacy have no bearing on the application of law according to this decision), he'd be entitled to $1.5 million on the first day.

That is not a bad ROI, that must be what the US Copyright Group was thinking with all those Hurt Locker suits in DC.

@Stan

"Go to a music shop and buy a new Fender guitar and amplifier, after you have parted with the $3000 you will have experienced your first in a long line of expenses that are associated with being a musician."

This used to be called paying dues, right?

Music is a product that nobody asked you to make. If you want to talk about this like "a business" you need to also consider the fact that music is a deeply stupid business to enter into. You've got 50-100k new competitors entering the field every single year and they all have the exact same business model? How is that a smart investment?

An education is no guarantee that you're learning, and buying equipment is only an investment if you did your homework first and already know how to use that equipment to make money. IT ALSO HELPS TO HAVE CUSTOMERS, real customers, not "Everybody loves music!" imaginary customers.

As a working musician I just want to say that labels are NOT the music business. You don't need a label to make music. You don't need them to record your record. You don't need them to get your music heard.

You need a label to put your CD in every Walmart in America and to get you on the radio.

Essentially, you need a record label to make you rich. These lawsuits are all about a bunch of rich people trying to stay rich or aspiring artists worried about losing their ability to become millionaires. It isn't about music or being heard or earning an honest living from music. There are millions of bands out there who would give an arm just to be on the radio. Not paid, just heard.

The sickest thing is that it has come down to suing teenagers and mothers and ordinary folks just to propagate that business model. I may not like people stealing my music, but I'd rather get a dayjob than sue my local high school so that I can maintain my cool $24,000/year from music.

I disagree with most of the posters here. Do you work for free? When you do your forty hours you do expect a paycheck don't you? Why should creative workers be any different? If you like my music,then buy it! Downloading music without paying for it is theft. I'm not doing this just so I can get heard on the radio and end up homeless! I've got almost $100k invested in my studio,and I didn't make that investment to give away the product that comes out of it. When McDonald's makes a million dollar investment in a new restaurant, do you expect them to give away every hamburger they make? Then why should I give away every song I create? I really don't care about what happens to thieves. If you break into a clothing store and steal all their merchandise, to me it's no different than stealing all of my merchandise off the internet. It's still theft! I ain't in this for the fun of it. If I create a product that people want,they should pay for it. I'd love to see this people get a little jail time.A thief is a thief,whether they use a gun or filesharing.

Hi,

I read today that the US supreme court will not give a hearing to the case.

I feel that the laws governing music piracy are breaking some basic principles of justice.

Making a person pay $750 for each track is outrageous.

If I steal a burger at MacD, will I be charged the cost of dinner plate at a expensive Manhattan restaurant?

Lets say MacD, Starbucks and some expensive restaurants have a association against food theft. Will they arrive at a average cost of theft or loss. They can't.

If I steal a Burger that costs $1, I can be made to pay $1+fine for trouble (to owner and society, not association of restaurants).

If I download 1 song that cost$1 at apple online music store, I can be made to pay $1+fine for trouble.

How can it come to $750, because the congress is in the pocket of corporates.

This amount reminds me of days when a Black man would be put in jail for sitting on a bench for Whites. US copyright law is same as apartheid laws and must be repealed.

Please correct me if I am wrong.

so, when does a person need to delete their music?

I realize these comments are old, but @NURREDIN - 1. These lawsuits are brought by record companies, not artists, over songs the artists get little, if any, royalties for, and the record companies have flat-out said 100% of what they win in these lawsuits or get in settlements goes into further litigation, not to the artists. It is simply not about the artists at all. 2. If your job is to nail hooks on walls, are you entitled to be paid every time someone hangs their coat on the hook? If not, then by your logic, those people are all "stealing" from you.

Look, the law does not entitle copyright owners or the artists who work for them to be paid, nor does it entitle businesses based on copyright exploitation a guaranteed livelihood, nor does it equate copyright infringement with theft, and the U.S. Supreme Court has even said as much. Rather, the law only sets penalties for not getting permission ('license') to make and distribute copies. If the copyright owner continues to hold that permission for an unreasonable ransom, offering nothing of greater value than the work itself, in the face of market conditions where content freely flows from person to person like water, then they deserve to watch their business of exploitation wither and die. They are slowly learning to compete with free, perhaps taking their lesson from the bottled water industry. Wouldn't it be grand if the water bottlers could say I "steal" from them every time I get water elsewhere...