June 28, 2010

June 28, 2010 Rock History: A Dialectical Narrative

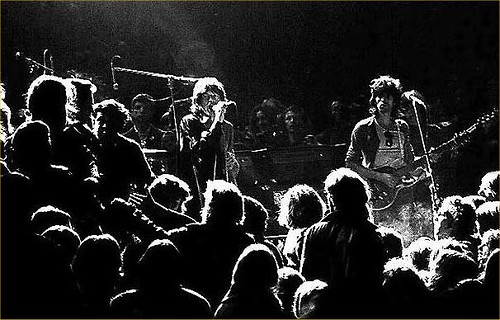

Photo via Rolling Stones Lyrics

The history of Rock music, like that of virtually any prominent cultural form, is constituted by a series of chaotic changes during its relatively short lifespan. From our own particular historical vantage point, more than forty years after rock’s “golden age” (roughly, the late 1960s), it is now possible to identify and ascribe cause to some of these historical changes. Of course, for any rock fan, the various narratives and value systems that make up rock culture are so familiar that they have assumed the shapes of reproducible clichés. The narrative of rock as music for the “rebel” has been reworded, reconstituted, and resold so often that it has required constant revision in order to remain fresh (and, by extension, to continue to fit into its own definition as “rebellious music”).

Unlike other cultural forms, however, rock occupies a unique position as the preeminent musical form of the era of mass media. The emergence and subsequent historical progression of rock has occurred almost coextensively with that of television. Consequently, rock, perhaps more than any other musical form, has been subject to commodification, its musical qualities often subsumed within its status as a cultural artifact and social tool. Piero Scaruffi writes that “’rock music’ was never a definition of the music, but a definition of the audience. Rock music was music for young white rebels.” In other words, rock has, historically, been defined more by its status as a cultural product, a set of social signifiers, than as a distinct musical form.

Any musical qualities that rock does possess tend to be particularly significant insofar as they relate to the production and dissemination of cultural narratives (including, but not limited to, the narrative of the “rebel”). The narratives and attendant signifiers that constitute rock have undergone a historical progression informed by continuous dialectical movement. Rock’s “golden age” represents a kind of “thesis” that established the narrative of the countercultural rebel. This historical era eventually hardened into a set of clichés, thus giving way to the “punk” era, which represents a sort of “antithesis” to the Golden Age by re-presenting rock as a negative image of itself, a new version of rock that defined itself through opposition to its own source. As rock proceeded toward the end of the 20th century, its own values became increasingly vague and ill-defined, a historical shift that constituted a sort of “synthesis” in which rock began to reject both its own definition as well as its own opposition to said definition. Today, rock artists continue to navigate a continuously shifting cultural landscape that seems to incorporate all of these cultural gestalts into its constitution.

I. The “Golden Age”

The “thesis” that is rock’s origin seems to have sprung from a kind of antithesis; and antithesis, that is, to a perceived notion of mainstream, “square” culture, an opposition to the life of conformity promoted by American suburbs and conservative political and sexual mores. The images and sounds of early rock, from Elvis’s censored pelvis to Little Richard’s coital yelp, served as indications that it was possible to escape the strictures of American culture and helped construct a cognitive, ideological basis upon which youth culture was able to build a self-identity apart from the mainstream. This process has been recounted endlessly in the pages of so many mainstream (and non-mainstream) publications that there is no need to continue to reiterate it here. What is important, however, is the extent to which these rebellious cultural impulses fermented into a set of reproducible clichés and cultural narratives.

If we fast-forward to rock’s “Golden Age” in the 1960s, we can see that rock’s rebellious impulses eventually “matured” into serious socio-political statements (sometimes explicit and sometimes implicit), which worked to shape the countercultural identities so prevalent during this particular era of American history. What is particularly significant for our argument here is the “sincerity” with which the artists of this era were able to make these statements, as well as the degree to which the signifiers produced by rock at this time “authentically” shaped the American counterculture. As we see in later era of rock, this “sincerity” eventually became nearly impossible to express in subsequent cultural milieus. During the “Golden Age,” however, it was perhaps the defining element and sentiment of rock music and rock culture.

This “sincerity” is not a simple case of artists “saying what they mean”; rather, it is a seriousness of purpose that pervades the music and cultural signifiers of the era. So many of the cultural signifiers of the era convey a sense of this serious, including the names of the era’s major artists. The Rolling Stones, for instance, were famously named in reference to a Muddy Waters song. Such a name indicates something “actual” about the content of the band’s music, namely that it is blues-based (or at least blues-influenced). Pink Floyd were, similarly, named after blues musicians, while The Doors were named after a line from a William Blake poem, presumably to underscore the band’s ostensible mission to open listeners’ minds and oppose cultural norms (as Blake did). This observation is not particularly striking until we begin to compare these names to those of more contemporary major artists, which are often intentionally mundane (Pavement, Shins), obtuse (Modest Mouse, Built to Spill), or sardonic (Replacements, Cat Power). Of course, to suggest that all artist names follow these kinds of patterns would be an unwarranted generalization, but the names themselves are not as important here as the specific cultural milieus within which these names enter into. I believe that “sincere” names such as the ones adopted by “golden age” musicians would fail to be taken seriously in contemporary times, as today’s musicians tend to strike more ironic poses (more on this later).

The “sincerity” of “golden age” rock is, more significantly, reflected in the content of these artists’ music and lyrics, as well as in widespread public perceptions of these artists. The protest music movement, of course, flourished in this era, in a way that would have been unlikely in today’s cultural milieu. Of course, political music has continually been produced throughout the rock era. What distinguishes the political music of the “golden age,” however, is once again the “sincerity” of the music, the seriousness of purpose with which artists of the era composed and conducted themselves.

Bob Dylan is, of course, the prototypical example of the rock protest singer, and so much of his early output (“Blowin’ in the Wind,” “The Times They Are a-Changin’”) has been received by the music-listening public as sincere statements of socio-political import. The archetype of the “protest singer” would eventually harden into a cliché, a phenomenon that Dylan himself seems well aware of, as his work during the later part of the 60s became increasingly obtuse and/or ironic. However, he continued to be perceived as a cultural figure of serious socio-political import. Subsequent figures have attained similar status, but it has rarely been for the “sincere” content of their music, but instead for their status as commercial, pop cultural figures (Michael Jackson, Madonna, Britney Spears) or as “negative” versions of seriousness (The Sex Pistols and the punk movement in general [more on this later]). Even satirical, ironic songs of the era tended to have a “sincere,” or serious intent. Country Joe and the Fish’s classic “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag” was a parody of older musical styles with satirical lyrics, but the song’s intent was to offer a serious (or at least semi-serious) critique of the Vietnam War.

Just as Dylan and other artists of his ilk were perceived as serious cultural figures, so many major artists of the “golden age” were serious musicians in ways that artists in subsequent eras were unable to be (or be perceived as). Jimi Hendrix is the prototypical example of the golden age “musician,” a status that is clearly justified by his performances. His rightly famous Woodstock performances show a man constantly pushing his musical craft toward new heights. Hendrix operated in much the same way that a great jazz musician did, using the art of improvisation to find new modes of musical languages appropriate to specific moments. Hendrix, as well as similarly-minded peers such as the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, stands in stark contrast to “great musicians” of subsequent eras. Eddie Van Halen was, arguably, technically superior to Hendrix, but he was not known as an improviser, and his work tended to fit into conventional pop structures. Even Phish, who are often compared to the Dead, tend to take a more ironic stance in their music. This is not to suggest that they lack musical talent or that they are not sincere, but that the musical and cultural landscape has altered in such a way that “sincerity” is perceived differently, perhaps more suspiciously (again, more on this later).

Of course, as I noted earlier, the musicals and cultural signifiers that constituted the musical culture of rock’s golden age eventually ceased to be fresh statements of socio-political import and became stale clichés. This is not a fact to be bemoaned, but simply a continuous historical tendency of human culture and language. As Richard Rorty says in Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, if a sentence is “savored rather than spat out, the sentence may be repeated, caught, bandied about. Then it will gradually require a habitual use, a familiar place in the language game. It will thereby have ceased to be a metaphor – or, if you like, it will have become what most sentences of our language are, a dead metaphor” (18). In other words, an original statement, when it is used often enough (or when it becomes culturally pervasive), eventually becomes a cliché, a “dead metaphor,” with a fixed meaning in language.

We see some of the first stages of this “deadening” process in the work of a counter-countercultural artist like Frank Zappa, who famously critiqued the culture of “golden age” rock, particularly on his 1968 LP, “We’re Only in It for the Money.” On this record, Zappa satirizes what he sees as the cultural clichés embodied by rock culture when, in the voice of an aspiring participant in the culture, says “I’m goin’ to a love-in to sit and play my bongos in the dirt.” The fact that Zappa was able to make such a statement indicates the degree to which the cultural signifiers of rock culture were “deadening,” becoming overused. Zappa is, of course, frequently cited as a spiritual and intellectual forerunner of the punk movement, precisely because of his critical stance on rock culture, a stance that punk would adopt (and which would itself become a cliché in time).

II. The Punk Era

The notion that the “punk” era of rock (roughly, the late 70s and into the 80s) was defined largely by a rejection of existing cultural norms has already been clearly elucidated in a multitude of publications. What is important to note here, however, is that “punk,” as a cultural notion, was able to arise largely because rock had by this point hardened into a set of reproducible clichés. Punk musicians and punk culture were able to define their own cultural identities largely by positing themselves in opposition to rock culture. Paradoxically, this opposition worked because it was able to position itself as a return to rock’s “original” notion of rebelliousness and cultural opposition.

As a cultural movement that defined itself through opposition, punk stands as a watershed moment in the dialectical historical movement of rock music and rock culture. This is precisely the kind of historical movement that Hegel discusses in the Phenomenology of Spirit when he writes that

What scepticism causes to vanish is not only objective reality as such, but its own relationship to it, in which the ‘other’ is held to be objective and is established as such, and hence, too, its perceiving, along with firmly securing what it is in danger of losing, viz. sophistry, and the truth it has itself determined and established, Through this self-conscious negation it procures for its own self the certainty of its freedom, generates the experience of that freedom, and thereby raises it to truth. (124)

What Hegel seems to mean here is that skepticism, by defining itself negatively in relation to something “other,” is able to generate its own truth. This is an essential part of Hegel’s historical process, and one that we see enacted in the punk movement. Whereas the major artists of the “golden age” tended to define themselves and their artistic projects “sincerely,” musicians of the “punk era” tended to define themselves in opposition to the cultural norms established by “golden age” musicians. Hence, “punk” era musicians tended to take up names that were intentionally ugly and/or confrontational, such as “Sex Pistols,” “Germs,” “Circle Jerks,” etc.

This “definition by opposition” is borne out in so many of the era’s defining cultural productions. Glen Matlock, the original bassist of the Sex Pistols, was rumored to have been fired for “liking the Beatles.” Whether this rumor is true or not is irrelevant here; what is significant to note is the fact the name “Beatles” had by this time become what Rorty describes as a “dead metaphor,” a signifier that meant, roughly: “an older era that we no longer want to be associated with.” Citing a love of the Beatles as a reason for dismissal was a perfectly acceptable linguistic gesture within the cultural milieu of the time. Similarly, The Clash, in the song “1977,” sang “no Elvis, Beatles, or The Rolling Stones/ in 1977.” Once again, the artist names cited here serve as signifiers of a bygone era, one which The Clash were defining themselves as “against.” America’s Minutemen took a somewhat more stoic approach to this process of self-definition in their classic 1984 song “History Lesson Part II” when, in a discussion of his musical idols (John Doe, Joe Strummer, and E. Bloom), lead singer D. Boon says “this is Bob Dylan to me.” Boon seems to be suggesting that his own musical idols are for him what a singer like Dylan was to musicians of the “golden age.” Here, the name “Bob Dylan” is used to stand in for the bygone “golden age” of rock as the band suggests that it has found its own idols to replace this era.

More significantly, the musical styles and signifiers that constitute the music of the punk era also work to define said era through its opposition to the music of rock “golden age.” It is well-known that punk culture has valued amateurism and “do it yourself” aesthetics. Paradoxically, these aesthetics often, at their most elemental level, resembled very closely the aesthetics of previous rock eras. The chord structures and melodies of the era’s major artists tend to be based on familiar blues progressions and pop melodies, however, they also tend to be played and presented with a sense of amateurism, or at least an oppositional sense of intentional “ugliness.” The early songs of the Sex Pistols and The Clash, the two defining artists of punk’s “codified” era, incorporate just such an aesthetic. Even as punk artists started to incorporate more complex musical elements, the music remained intentionally “ugly.” This strain of punk music is exemplified by the later work of Black Flag, who incorporate dissonant guitar melodies into song structures inspired by American jazz music, and is perhaps best exemplified by the prominent “no wave” artists of New York, who stressed dissonance as a musical element. These artists stand in stark contrast to “golden age” artists; Hendrix’s music, after all, was often dissonant and noisy, but it always remained “sincere,” rather than intentionally “ugly.”

The new musical “language” spoken during the punk era was clearly meant to oppose the “language” spoken during rock’s “golden age.” These twos eras managed to development contrasting “language games” that came into conflict with one another during the historical transition between said eras. Jean-Franҫois Lyotard, in The Postmodern Condition, defines a language game (by way of Wittgenstein) as a sort of linguistic structure in which “each of the various categories of utterance can be defined in terms of rules specifying their properties and the uses to which they can be put – in exactly the same way as the game of chess is defined by a set of rules determining the properties of each of the pieces” (10). In other words, language (which can include any form of communication, including music) operates according to a set of rules, rules which are continually renegotiated in order to specify what can and cannot be stated within a specific cultural milieu.

Punk, in its effort to define itself through opposition, constituted a shift in rock’s “language,” a new “language game” that rock began to operate within. The disjunction that existed between the “old,” “golden age” language game of rock and the “new,” “punk” language game is exemplified in a 1977 Rolling Stone interview in which “golden age” rock star Stephen Stills was asked for his opinions on some of the new records of the day. Commenting on the Ramones’ song “Sheena Is a Punk Rocker,” Stills says “This is that punk shit everyone’s going nuts over? Sounds like four 6-year-olds picking up instruments for the first time. This sucks.” Commenting on The Clash’s “White Riot,” he says “This is worse than the one you just played me. Whatever happened to singing?” Stills’ lack of appreciation for these songs is, of course, not a result of a lack of musical acumen; it is, rather, the result of his operation within an older language game just as the new, “punk” language game was coming to take its place in the popular consciousness. The singing that appears on the Clash record may not succeed according to the rules of the old language game, but it was appropriate within the context of punk’s musical “language.”

Of course punk, while it offered a possibility of opposition to the cultural and musical norms established in the “golden age,” was also subject to many of the same historical changes. Eventually, the oppositional stance of punk became, itself, a cliché, and by 1978, the Crass were declaring on record that “Punk Is Dead,” a refrain that would come to be repeated (and denied) repeatedly. Of course, by time the early 90’s rolled around, punk’s oppositional stance had become acceptable enough to become commercially viable. This left forward-thinking musicians to attempt new responses in order to continue to push forward original ideas in rock music and rock culture.

III. The Age of Irony

As punk’s oppositional stance became a cliché, or a “dead metaphor” in Rorty’s terms, rock’s capacity to comment meaningfully on the outside world seemed to be exhausting itself. As rock progressed forward, many of its major artists responded by ceasing to attempt to actually say something “meaningful” about the world and instead adopting an ironic stance toward the music-making process. Of course, it has already been well-documented that ironic attitudes have been predominant in the youth cultures of generations X and Y. In the realm of rock music, these ironic attitudes seem to have emerged largely through a self-conscious integration of both the “golden age” paradigm of “sincere” music and the punk paradigm of “oppositional” music. Many of the major rock artists of this era referenced elements of both paradigms while taking neither entirely seriously.

Pavement, while not the most commercially successful band of the era, probably best exemplify the ironic turn that rock eventually took. The band was widely known for their “slacker” approach to music; the TV characters Beavis and Butthead reflected this approach when they commented during a Pavement video that “these guys should, like, try harder” (quoted from memory, so it may not be entirely accurate). This is not to say that the band wasn’t “trying” or that they weren’t “sincere.” Rather, the signifiers that constituted their music generally embodied a kind of ironic take on rock as it was constituted at the time. What is truly significant here is that the musical and vocal styles of a band like Pavement could be received as serious within the cultural milieu of the early 90’s in a way that they could not have been received in earlier eras of rock. On the other hand, the “sincere” styles of “golden age” artists could not have been perceived as sincere during this historical era, because they had already become clichés.

Pavement’s music, while it displays a strong sense of song craft, frames this very sense of craft in an ironic light. The vocals proceed in a kind of flat, monotonous style that was not often heard before this era. This vocal style (heavily influenced by bands such as REM) has continued to be influential, as major rock artists such as Broken Social Scene and Modest Mouse have employed similar style. The singing on a Pavement record is an ironic take on traditional rock styles. This ironic take extends to the basic elements of the band’s music; Pavement employed traditional rock tropes (such as the I-V-VI chord progression of “Summer Babe”), but plays them in a kind of “detached” manner. This “detached” manner differs significantly from the “oppositional” stance of punk. Whereas as punk adopted the musical tropes of rock to oppose its hegemonic cultural stance, an ironic artist such as Pavement appropriates many of these same tropes, but does so in a kind of playful manner.

In a seemingly opposite vein, Nirvana, the major commercial rock force of this historical period, seemed to present a new kind of intense sincerity in their music. This sincerity seems, at first glance, to hearken back to the sincerity of “golden age” rock artists. The difference, however, is that Nirvana’s sincerity (a kind of sincerity that would proceed to influences a countless number of artists) is more self-reflexive; rather than address the problems of the world, it addresses the problems of the self, but in a somewhat obtuse manner. It is hard to imagine a “golden age” rock artist singing a line like “I’m so happy, ‘cause today I found my friends/ They’re in my head.”

The band’s musical signifiers also embody these self-reflexive properties, which have continued to hold sway over entire subsequent veins of rock culture. The band’s vocal styles are, on the surface, nakedly emotional, employing high-volume screeches and unchecked vocal tics (which can be traced back to “naked” records such as Neil Young’s classic “Tonight’s the Night”). These kinds of screamed vocals have continued to show up in strands of rock such as the various incarnations of “emo,” and they demonstrate a significant shift in the way that rock vocals are perceived. Singing has always, presumably, served as a way to represent human emotion. By this point in history, however, it seems that much of the listening public was skeptical of singing, believing that it wasn’t “real” enough. Screamed vocals seem to present to the listening public a style that is more “real” in that seems to be a more direct expression of emotion. Of course, the paradox that we see here is that these vocals, in spite of their apparent “realness,” remain a mere representation of emotion, and not the emotion itself.

What the music of both Pavement and Nirvana (and, perhaps more significantly, a whole host of artists contemporary to and/or influenced by these bands) have in common is a sense of detachment from direct interaction with the outside world. In the case of Pavement, this sense of detachment takes on the form of irony, the ability to not take existing form of rock expression seriously. In the case of Nirvana, this detachment takes the form of self-reflexivity (with its own healthy dose of irony), as the band sang of the trials and travails of angst with occasional seriousness and occasional self-deprecating winks (such as the song title “I Hate Myself and Want to Die”).

These artists also share an ability to appropriate familiar rock tropes in a way that simultaneously aims for serious musical expression and ironic detachment. The chord progressions and melodic phrases that the artists of this era employed aimed to both “hook” listeners in the same way that the music of “golden age” artists had, while at the same time displaying an ironic detachment from the seeming limitations of these very structures. The Pixies, one of the central artists of this era, famously formed out of a want ad asking for musicians who were fans of both Hüsker Du and Peter, Paul, and Mary. The references in this ad to both a paradigmatic “oppositional” punk band (Hüsker Du) and a “golden age” folk group (PP&M) highlight this dichotomy. These artists aimed to employ traditional rock song structures into their music, as well as the very opposition to said structures. This has lead to music that is both “noisy” (in accordance with the “language game” played by punk music) and “sincere” (in accordance with the “language game” played by “golden age” rock music). It is important to note that within the cultural milieu of this era, neither an oppositional nor a sincere stance carries the same validity as it originally did, as both stances are not taken entirely seriously.

Modest Mouse was a band that came into its prime towards the later half of the 90s, after the aforementioned artists, but they came to crystallize some of the ironic, yet personal statements that this era of rock came to make its own. In the song “Interstate 8,” band leader Isaac Brock sings: “I drove around for hours, I drove around for days/ I drove around for years and months and never went no place.” Here, the band expresses a sense of meaninglessness (“I never went no place”), but makes this meaninglessness personal through the constant self-reference to the artist’s own driving. The band has also made fascinating socio-political statements; unlike the “sincere” artists of rock’s “golden age,” however, these statements tend to convey a sense of detachment from their source. In “Teeth Like God’s Shoeshine,” the leadoff track from their classic 1997 album “The Lonesome Crowded West,” the band sings “The malls are the soon to be ghost towns/ well, so long, farewell, goodbye.” This apparently anti-capitalist statement is couched not in the vocabulary of reform, but in that of stoicism; rather than call for a destruction to the consumerist culture of the mall, the band shrugs off said culture, seeing its dissipation as an inevitability.

IV. Today

Rorty suggests that the changes occurring in language games are constantly accelerating, and as we survey the musical landscape of rock today, this seems to be the case. So many major artists seem to be re-appropriating “sincere” vocal styles, such as Grizzly Bear and the Fleet Foxes. These artists implement their styles in a way that is, to my ears, truly exciting, and yet also self-conscious, in a way that the music of “golden age” artists was unable to be. Ultimately, what we seem to be hearing in the contemporary era of rock music is a synthesize of the style’s multiple incarnations. The aforementioned artists, as well as other significant groups (such as The Arcade Fire, Broken Social Scene, Animal Collective, etc.) all incorporate musical tropes from all of the various eras of rock history. They tend to be, in their own way, “sincere,” while at the same time displaying opposition to musical norms.

This new era seems to have harvested a veritable treasure trove of artistic talent. Of course, as Hegel and other skeptical historians have noted, any historical is uniquely situated, and is contingent on the eras that came before it, as well as on its own unique cultural environment. What I ultimately hope to have demonstrated here is that rock music has, on the one hand, continued to generate exciting and unique cultural productions and has, on the other hand, depended on historical and cultural situations and environments in order to generate these specific brands of creation.

Eric Casero is a graduate student with a Master’s degree in English literature. His interests include modern and postmodern literature and culture, and the relationship between culture and the human brain. He will begin studies at Kentucky University in the fall.

He is also the author of the fantastic Pop Matters essay: Mental Machine Music: The Musical Mind in the Digital Age.

Reader Comments (9)

I'm with Stephen Stills.

This is a rather chewy piece. I felt like I was reading a college thesis.

This is not intended as a slam, btw, I read it all the way through after all. It's just that I'm not sure what to make of it as regards navigating one's way through todays music biz landscape. I've been reading MTT since its inception and I don't recall a piece of this nature. (I could be wrong, of course. Have been before, will be again.) I'm still trying to make the mental adjustments between what I expect to read here and what I perceive this to be. Maybe I just missed (or didn't understand) something in the aim(s) of MTT.

That being said, I did enjoy it. Whether I'm right or wrong on how I interpreted MTT's goals, I'd read more posts of this nature and, in fact, as soon as I hit "Create Post" I'm heading over to read Mr. Casero's "Mental Machine Music: The Musical Mind in the Digital Age."

It doesn't matter if it's pointed at a sort of "how to do something career enhancing in today's music biz" tip or not, it's good to be challenged to think a bit. All of us are "standing on the shoulders of giants" and getting a perspective on where we -- personally or as a "community" -- are coming from can only be positive.

That might be the "takeaway" from this piece for me. If I'm not capable of defining where I stand on my musical presentation, how am I supposed to convince some nice venue to hire me?

(hmmm... that might have been a whole buttload of words just to say, "good post!".)

@Howlin' Hobbit

I am the new Editor / Community Manager here at MTT, taking the place of Bruce Warila. Your quite right in your observation that this piece lies outside of the typical narrative that you would expect to find here at MTT.

As well, you've explained my goal is posting this essay quite well—the idea was to broaden the range of discourse that one might expect here and to put out something challenging. A piece that provokes a little deeper introspection. I believe this is a great form to help artists enhance their careers in this chaotic industry and also felt like the readership may like pieces this as well—even if it is a little academic.

Glad to hear that you've enjoyed Eric's post and didn't think that it was completely out of place. There will certainly be more and more of what you'd normally expect here—from a wide range of great authors. With that, I will also try to nurture some new authors, like Eric, who are interested in expressing some bigger ideas and engaging in some cultural criticism. I found Eric over at Pop Matters and loved his piece that he posted there—that's why I've since brought him here and let him express more of his ideas.

Hope this clears everything up and thank you very much for commenting.

-Kyle

Artists need to create an anti-environment to mirror back where their culture is at. The technology was new, the players were new, but rock, like any other "genre" is just re-playing the same archetypes human culture has always been working with. We still have Sun Gods and we still sacrifice them, too.

Speaking of "The Age of Irony" -- how many of the artists you reference here were remotely conscious of the larger implications and causes of what they were doing?

Yep....

When the academics explain it, the party is long over.

Along with sincerity, there was also the concept of originality. I agree with many of the concepts laid out throughout this piece about the 'sincerity' of rock music, how it used to be and how it is becoming once again, but originality also played a heavy hand into what made rock n' roll edgy and rebellious. Looking at bands like Led Zeppelin, who were edgy, rebellious, and original, but were also the center of their own universe. Im not sure I would consider their 'The Song Remain The Same' movie a work of sincerity, what with the dream sequences, white horses and shiny clothes. It seems that throughout rock history, sincerity and originality were equal counter-parts, that if a band did not possess one characteristic, they surely possessed the other.

Though I will admit, that in today's world of 'rock music', originality is harder to come by, so sincerity is a welcome return.

One thing this essay could have used was an exploration of how modern rock became the context-free and meaningless heap of macho noise that it is today.... while still being the most popular form of "rock."

Eric is correct when he writes about Pavement and Modest mouse being representative of the 90's irony zeitgeist. But when these bands were playing shows for a few hundred people, bands like Creed, Korn, and Limp Bizkit were beginning to emerge as MTV's torchbearers of rock. Or go back to the 80's - postpunk may have been where are the meaningful music evolution took place, but it was Hair Metal that was bringing in the rock dollars.

I think it goes all the way back to Punk. At that point, there was a fundamental disconnect between what was important\interesting, and what was popular. Only in the "Golden Age" did the two manage to coexist in the same music scene. Since then, to an increasing degree, people have liked less interesting music.

This is why irony and authenticity have become such awkward touchstones in Indie rock. This is why "music doesn't mean what it used to." There is no social context for listening to good music anymore. Groundbreaking rock is appreciated by the minority, while everyone else just listens to Nickelback. No wonder detachment and irony are all that Indie musicians have left.

Neat summation of a mess, with many statements I would disagree with. Basically, I have this theory that you can tell someone's musical taste and a certain amount about them from how they relate pop history. I smell math rock. That gives Eric an axe, the sound of which grinds right through.

How you can write a piece like this and barely touch on music made by black artists, either from the States, UK or W Indies amazes me. And if you would like to see self-aware irony in action during the apparently more authentic 'golden age' you could start off with reading Absolute Beginners by Colin MacInnes, Tarantula by Bob Dylan and the lyrics to a range of Beatles's songs, from Revolution to Norwegian Wood. Many artists, from the Monkeys to The Stones knew exactly what their place was, unless you credit Jagger with genuine revolutionary beliefs (check the story of the Stones tour that led to Alltamont for a story of breathtaking cynicism and ego)

And surely you have to acknowledge the cultural differences between the UK and the USA where punk came to mean crazily different things, let alone the direct language (or, at least, 'accent') collisions.

Too neat, for me. But good point about the major cultural explosions being a world away from critical pop history, Justin. A quick trawl through the decade's sales figures will always put some context on the bones: where sits Engelbert Humpledink? Where sits The Birdy Song and Olivia Newton John? How ironic was the Van Halen solo on Michael jackson's Beat It? (Were the metallers having a laugh?)

And Led Zeppelin, original, Jon? I think they were like the Sha Na Na of heaviosity, a little bit Who, a little bit Cream, a little bit 13th Floor Elevators, a little bit Blue Cheer... and a lot of a whole bunch of blues guys, many of whom are still waiting for their royalties. Now that IS ironic.

Yeah, I'm on Team Tim. To include the quote "Rock music was music for young white rebels" is both a bold and troubling statement. To a degree, I see how the music/culture made from the sufferings of people from the African Diaspora has influence many major musical stylings. Blues origin steming from Western Africa, Blues influences UK bands, Chuck Berry's Rock N' Roll, Jazz, First Wave Ska as the choice of music for the "Kitchen Sink" youth of the UK, and many more.

I remember in my philosophy classes in college that the new popular discourse include race and gender. As I did enjoy reading this piece(because I learned a new way to look at our past), your discourse lacked the issues of race & gender. Or atleast, acknowledging its presence and stating why you choose to ignore it or otherwise.

-iBeat