February 6, 2019

February 6, 2019 How Imagine Dragons Writes Memorable Melodies

Guest post by Hunter Farris. This article originally appeared on Soundfly’s Flypaper

What gets us to remember a tune?

Have you ever remembered a song well enough to sing along to it the next time you heard it? Maybe you didn’t know the words, but you could at least hum along. Or have you ever played “name that tune”? What made you win some rounds so easily and yet lose others? One answer lies in how, precisely, the melody is set up.

I’m going to be honest: I was fully prepared to write this article about how Imagine Dragons’ “Demons” is the wrong way to write a song. But then I went to the mountains of Utah on a weekend camping trip with my church group. A few of us had split off to sing songs with a few guitars. You know them all: “Hooked on a Feeling,” “Don’t Stop Believin’,” “Something Just Like This,” and plenty of others. I knew people would sing along to those, but what about these epic, anthemic contemporary pop songs like those of Imagine Dragons?

Surely, eventually, curiosity got the better of me, and I started to play “Demons” to see what would happen. And everyone sang along as if it were a tune they’d all grown up with all their lives. That’s when I had to wonder: Why do people always remember the melody to this song?

False Sequences

One reason people can’t help but remember the melody here is because it’s riddled with what are called “false sequences” — a melodic technique that gives us a feeling of relative novelty, and that relative novelty makes the song more memorable. What does this mean?

Well, let’s start with a normal melodic sequence, which The Oxford Companion to Music defines as: “The more or less exact repetition of a melody… higher or lower.” For example, “Do-Re-Mi” from The Sound of Music plays notes 5 1 2 3 4 5 6, then brings every note of the melody up one pitch higher so that we hear 6 2 3 4 5 6 7, then again, one pitch higher to give us 7 3 4 5 6 7 8.

“Demons,” like many popular songs, puts a twist on that idea with a false sequence. In the third book of his series, A Theory of All Music, Kenneth P. Langer defines a false sequence by saying it “contains some notes of the original [tune] but not all. It appears, at first, to be repeating but changes.” It falsely pretends to be repetition, then pulls the rug out from under you to reveal a sequence, and this kind of false sequence is the basic premise this song’s melody relies on.

You can hear this play out in the first verse when we get the same melodic run played twice in a row. We hear these notes on a scale: 1 1 5 2 2, and then: 1 1 5 2 2. The very next phrase “appears, at first, to be repeating” when it starts out with the same two tonic notes, but then changes by moving the next two notes up so that instead of 5 and 2, we get 6 and 3. It’s a perfect example of a false sequence.

In the chorus, the band brings this technique right back in. We hear the notes: 3 3 5 1 7. The next phrase appears at first to be repeating when it plays 3 3 5, but then changes its resolution by finishing off with 7 and 6.

Relative Novelty vs. Absolute Novelty

Those false sequences give us listeners a sense of what psychologists call “relative novelty,” as opposed to “absolute novelty.” Relative novelty isn’t about being exposed to all new stuff — it’s about being surrounded with things that are familiar but with an occasional novel bit. We don’t remember the melody because it’s familiar; we remember it because it’s novel, but not too novel.

If you repeat everything, it gets boring. And if you changed everything, it would feel erratic.

It’s kind of like if you changed one little part of your usual route to work or school, but kept everything else the same. This kind of relative novelty is what “Demons” purveys. This song doesn’t want to slap you across the face with something new every time around the progression. It wants to give you a bowl full of familiarity with a spoonful of novelty mixed in there, and it does a great job.

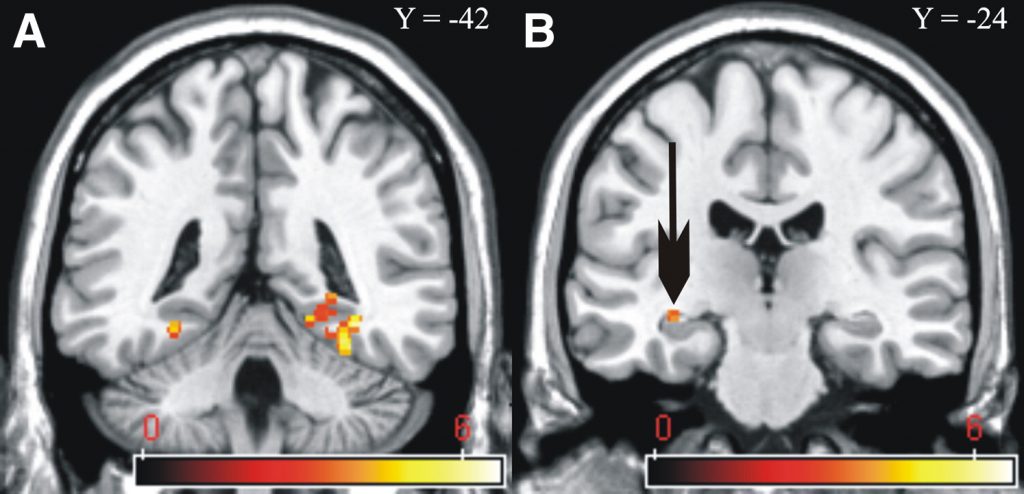

When they were working together at University College London, researchers Nico Bunzeck and Emrah Düzel ran an experiment where they showed people ordinary pictures — normal areas, normal faces, normal landscapes — but occasionally threw in an “oddball” picture. They measured those people’s brains using an fMRI machine and found that people’s pleasure centers generally lit up with dopamine when they saw something novel.

But that only really works with absolute novelty, like how Queen‘s “Bohemian Rhapsody” puts the breaks on its opera section to bring in a hard rock section following it, or like looking at pictures of soda cans and then seeing a picture of Niagara Falls.

“We thought that less familiar information would stand out as being significant when mixed with well-learnt, very familiar information and so activate the [pleasure center] just as strongly as absolutely new information. That was not the case. Only completely new things cause strong activity in the [pleasure center].”

Yet while relative novelty didn’t bring more pleasure, it did cause better memory retention. Dr. Düzel and Dr. Bunzeck tested this by showing people three groups of pictures: pictures that were all familiar, pictures that were entirely novel, and pictures that had some familiarity and some novelty. Twenty minutes later, they checked how well the participants remembered those groups of pictures, and found that the mix of novelty and familiarity was 19% easier to remember.

“This study shows that [developing memory] is more effective if you mix new facts in with the old. You actually learn better, even though your brain is also tied up with new information.”

In short, relative novelty is one of the keys to memorability.

In the lab, Bunzeck and Düzel found that a mixture of novelty and familiarity works best as a recipe for getting us to remember something. And out at camp, I found that a mixture of sequence and repetition works just the same. Imagine Dragons uses false sequences in “Demons” to help us remember its melody faster, and for longer.

Songwriting tagged

Songwriting tagged  composition,

composition,  melody,

melody,  songwriter,

songwriter,  songwriting,

songwriting,  writing

writing

Reader Comments