October 14, 2021

October 14, 2021 The secret grammar of music

Guest post by Dale McGowan. This article originally appeared on Soundfly’s Flypaper.

I was 13 when I saw my brother’s college music theory textbook sitting on a table — Walter Piston’s Harmony. I had played clarinet and sax for a while, even did some arranging for jazz band. So I knew a little theory, but I was barely out of the blocks.

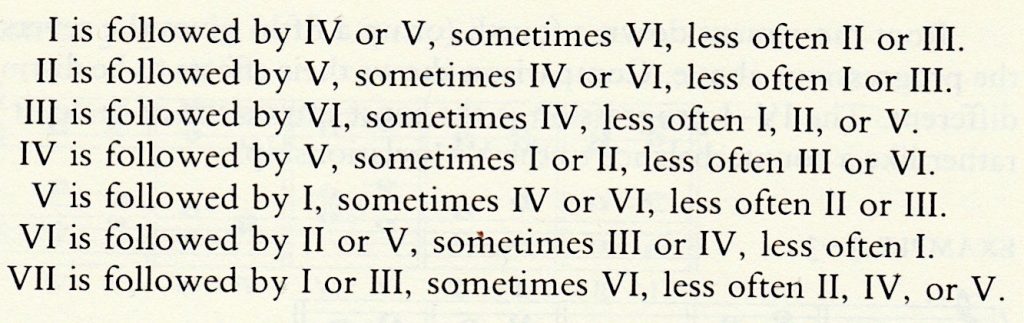

When I picked up the book, it fell open to a section called “Table of Usual Root Progressions.” Clickbait! I traced the words with a trembling finger:

![]()

(That’s an actual scan of the actual line in the actual book.)

Whoa.

If I’d known less theory, I’d have glossed right over it without understanding what it meant. If I had known more, I might not have been surprised by it. As it happens, I knew just the right amount to be gobsmacked.

It continued:

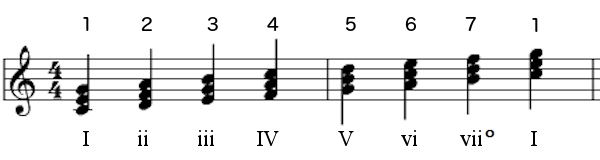

Here’s what it’s saying. Every key has 7 triads in it — 7 chords based on the 7 notes of the scale for that key. This is C major:

Now look down the left side of the Piston text: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII. These are the 7 triads of any key. (If you know some theory or read this post, you’ll know the Romans are usually upper case for major and lower case for minor. He’s making them generic for this example. Be not confused.)

Each line is saying, “When you hear this chord, here are the chords you’ll most likely hear next.”

So for C major, you could rewrite the text like so:

The C triad is followed by F or G, sometimes A minor, less often D minor or E minor.

The D minor triad is followed by G, sometimes F or A minor, less often C or E minor.

And so on.

Here’s the thing: I had no idea there was a “most likely” order of chords. If I’d written a theory book when I was 13, it would have said:

Chords are nice because they make the music fuller than just a tune alone. If you’re in the key of C major, the C triad should be followed by something different, because variety is the spice of life. GENESIS RULES! DM + KH 4EVER.

I saw the chords as 7 different colors the composer could use, and yes, they are that. But it never occurred to me that there was this kind of hidden sense to it, a kind of grammar, like saying: “The subject is usually followed by a verb, sometimes by an adverb, less often by a prepositional phrase.”

It was my first real glimpse below the surface of music. And then Piston did something lovely and rare in music theory — he explained why it’s that way.

When you move from any triad to another, there are only three possibilities: the chords have two shared notes, or only one, or none at all:

Each of these has a different emotional quality. The first one is called a “weak” progression (though never to its face) because there’s only that small change between the chords, just one note different while two hang on. It’s like a sloth working its way through the forest canopy, moving just one limb at a time while the others stay attached.

When the roots of the chords (the note on which it is built) are a third apart, like C to E, you get that progression.

“Weak” doesn’t mean bad — sometimes a weak progression is just what you want for a tender moment, like so:

Here it is put to perfect use:

If all of the notes change, the feeling is more abrupt. There’s no connection between the chords. There isn’t a sense of smooth harmonic direction because the connection to the previous chord isn’t there. It’s a monkey leaping from one tree to another. You can’t easily tell where he leapt from.

When the roots of a chord are a second apart, like C to D, you get this kind of progression. The chord change at 0:38 is this type:

And then there’s the engine that drives music.

This is for chords with roots a fifth apart, like G and C, dominant to tonic. It’s Goldilocks, not too weak, not too abrupt: one note shared, two notes changing. It’s the perfect balance of continuity and dynamism, the monkey brachiating effortlessly through the rainforest of your mind, one hand back on the previous branch, a hand and a foot reaching forward to the next. And on he swings.

It’s called a circle progression for a great reason I’ll get to eventually.

When a composer wants you to feel direction on a large or small scale, the circle progression is the go-to. It flows like water. This aria from a Bach cantata is as good an example as any. The circle starts at 0:17 and ends around 0:30:

Do you feel how the harmony was essentially marking time at the beginning, then starts rolling forward at 0:17? Circle progressions will do that to you.

The big news here is that harmony is spinning out a narrative beneath the melody. Composers use a mix of the three types of progressions to create an ebb and flow — moving forward, circling back, pausing, lurching, and sliding effortlessly in turn.

Now if you look back at the Piston text, it starts to make sense. No matter which of the 7 chords you’re on at a given moment, the most likely next step is a circle. That Bach progression is:

I – IV – VII – III – VI – II – V – I

That’s all circle, and you can feel the tumbling momentum. But sometimes you don’t want that, so you’ll move by second or third, depending on the musical need of the moment.

Like all grammars, the real fun comes in busting out of the box — chromatic harmony, secondaries, modal harmony, polytonality, atonality, jazz harmony — but that page of Piston’s Harmony was my first step into the basic grammar of Western music. And it totally changed the way I saw my favorite thing.

And if you’re interested to learn more about how to add jazzy chords and melodies into modern pop and hip-hop songs, you’re going to love Soundfly’s new course with pianist and beat producer, Kiefer, on keys, beats, and chord changes, coming this November! Hop on our mailing list to be notified when this exciting course drops!

Don’t stop here…

Continue learning about music theory, composition, arrangement, and harmony with Soundfly’s online courses, like Unlocking the Emotional Power of Chords, Introduction to the Composer’s Craft, and The Creative Power of Advanced Harmony.

—

Dale McGowan has one foot in arts, the other in sciences, and the other in nonreligious life. He double-majored in music and evolutionary anthropology at UC Berkeley, then studied film scoring at UCLA before conducting a college orchestra while earning a Ph.D. in Composition from the University of Minnesota. Dale is managing editor of nonreligious writers at Patheos, the world’s largest website for multi-belief opinion. He teaches music at Oglethorpe University, is at work on a book about how music communicates emotion, and hosts the How Music Does That podcast.

Music Research,

Music Research,  Songwriting tagged

Songwriting tagged  composition,

composition,  music theory,

music theory,  songwriting

songwriting

Reader Comments