October 14, 2021

October 14, 2021 The birth of unjazz

Guest post by Ben Morss of Soundfly’s Flypaper. This article originally appeared on his Rock Theory Blog

This winter, walking my dog in the snow, listening to Spotify’s Top 50 playlist, I heard something striking: a lovely jazzy instrumental touched with pretty jazz guitars, the sound of birds and faraway kids playing, topped by a beautiful, timelessly wandering vocal.

Melodic ideas repeated, but the song didn’t have a clear focus or drive toward a chorus. The vocals soared ridiculously far above the bass. I begged my dog to stay and checked my phone. What was this song, and what was it doing in the Top 50?

It was the latest from SZA, called “Good Days.” I resolved to learn more.

While pondering “Good Days,” I remembered a recent discussion in the Soundfly community about Rihanna and Drake’s 2015 collaboration “Work.” The question was: what key was this song in? I maintained that it was in C# minor, even though the song uses the B major scale (or G# minor, if you prefer) and its melody emphasized notes like F#. But those who said the song was in B or E had equally good cases.

Why did my heart tell me C# minor? I needed to investigate!

After a couple of months of listening and thinking, here’s what I’ve learned: R&B singers, rappers, and producers have been busily creating something I call “unjazz.” They’ve found ways to introduce, right into the Top 40, a previously unthinkable level of harmonic ambiguity and tolerance for melodic dissonance.

Unjazz? Why “unjazz?”

Because while I believe this musical idea is rooted in jazz, I don’t think it sounds like jazz, and plenty about it is foreign to jazz. And yet, in many ways it’s similar to jazz, too.

I believe it all began in the mid-1990s, as the sound and approach of hip-hop music permeated R&B. In the late 2000s, when rappers began to sing more, they reached back to what they’d heard R&B singers do, but in a whole different context. Some of them ended up emphasizing scale tones like the 9th, the 11th, and the 6th — pitches that would have previously been treated as dissonances. But, for these rappers, they felt right. And listeners loved it. Finally, completing the circle, the singing rappers influenced R&B singers, who took the new melodic freedom and ran with it.

First we’ll look at the starting point: harmonic ambiguity and dissonance treatment in pop and rock. We’ll see how jazz harmonies have come back into the Top 40. But then we’ll trace how a whole new jazz-influenced school of harmonic ambiguity and dissonance made its way into R&B, hip-hop, and ultimately the pop charts. We’ll make our way to TLC’s “No Scrubs,” and then revel in the innovations of Drake, touching on two choice tracks of his from Nothing Was the Same.

And if you’re interested to learn more about how to harness the intersections between jazz and modern hip-hop in your own music, you’re going to love Soundfly’s newest course with jazz pianist and beat producer, Kiefer, on keys, beats, and chord changes, coming this October! Hop on our mailing list now to be notified as soon as this exciting course drops.

The Status Quo — What Is Dissonance?

Before we can talk about dissonance, we need to define it. When I say “melodic dissonance,” I don’t mean people singing out of tune, or in a raspy voice. I’m referring specifically to the concept that two pitches, heard together, can sound more dissonant or more consonant.

It’s important to note that “dissonance” is strongly determined by culture and context. A given harmony could sound more or less dissonant to different people in different cultures or simply different contexts. That said, most listeners will regard two pitches heard together as more consonant when the frequencies have a simpler ratio.

If pitches are an octave apart, the frequency ratio is 2:1. That sounds highly consonant! For pitches a fifth apart, the ratio is 3:2, and the fifth is almost always regarded as consonant as well.

Pitches a fourth apart have a ratio of 4:3. With this slightly more complex ratio, this interval is a dissonance in certain contexts and a consonance in others. Oddly, although thirds are an even more complex 5:4 or 6:5, they’re more typically consonant in Western music, likely because thirds are part of the overtone series. For example, in Renaissance polyphony, the fourth was a dissonance that needed to resolve down to a third, like this:

Audio Player

Your modern ears almost certainly didn’t hear that fourth as dissonant. But if you listen carefully, you’ll still feel a bit of tension when you hear the fourth, and you’ll feel it resolve when you hear the third. In fact, as we’ll see, the fourth tends to be a melodic dissonance to this very day.

In Western classical music, until the 20th century, dissonances were well defined, and they were normally resolved by a set of standard techniques like this one. These formulae have long been codified and given names like the suspension and the passing tone.

In pop music, melodic dissonances are treated more loosely, but as these techniques still resonate in our ears, we will refer to them in this article. You can read more about them here or here. If you want to learn even more about consonance and dissonance, Soundfly’s courses, Unlocking the Emotional Power of Chords and The Creative Power of Advanced Harmony will set you up nicely!

But don’t forget that consonance and dissonance are determined by expectations governed by culture and context. Composers of atonal serial music tended to avoid the octave. In the context of highly dissonant music, a sudden consonance would stick out. Dissonance is in the ear of the beholder! And that point is central to this article. Because, right now, modern rap and R&B are training our ears to hear as consonances certain things that we would have previously considered dissonant.

They’re pushing the harmonic envelope, expanding what’s possible in pop music.

Roughly speaking, pitches that are in the current harmony are consonant, and others are dissonant. A lot of pop music uses only major and minor triads, where the 1st, 3rd, and 5th scale degrees are consonant. Another way of looking at this is that those are always consonant and everything else is always dissonant. So, if the current chord is C major, C, E, and G are consonant, but we’d expect a D, F, A, or B to resolve. That’s the 2nd, 4th, 6th, or 7th. These notes would want to resolve stepwise to a neighboring consonance — just like the 4-3 resolution we played above. 7-8 is another classic resolution, like this:

Audio Player

Today’s singing rappers and R&B singers use a variety of new ways to treat dissonance – either to resolve it or to simply normalize dissonances as consonances that require no resolution. As we see these phenomena in examples, we’ll describe each with a standard phrase. For clarity, we’ll underline each phrase and assign each a characteristic emoji.

So:

- consonant once, consonant again: taking a tune that’s consonant over one chord and reusing it over chords where it’s dissonant.

- stick with your scale: using the same scale over all chords, whether it would traditionally fit or not.

- singing the “wrong” scale: choosing a scale that doesn’t quite match the chords, unless you’re thinking about traditional dissonances as consonances.

- normalizing dissonant pitches as consonant: training us to hear a traditionally dissonant pitch like the 6th as a consonance.

- elevated scale degrees: prolonging the 7th, 9th, or 11th until we hear it as a consonance.

- ☰ ladder of thirds: climbing up or down a ladder of thirds to normalize the 7th, 9th, and 11th scale degrees. This ladder may well descend to the 5th and 3rd.

We’ll also see harmonic ambiguity of a sort rarely seen in Western pop before. Here are two categories, with their phrases and emoji:

- harmonic ambiguity: we’re obscuring the chord progression or never defining it clearly, and we’re fine with that.

- root in the voice: the voice contains the chord root, or, better still, as it’s louder and deeper than other sounds, it changes the root from what the instruments implied.

To sum up: even as modern pop incorporates jazz harmonies as they were used in 1970s funk and pop, adventurous R&B and hip-hop musicians have been extending pop’s harmonic language in ways that go beyond these influences. They’re exploring things that would have previously been regarded as dissonance, leaning into these dissonances and making them into new consonances in a way that I think has ever occurred in the Top 40.

To see what I mean, let’s start by considering how dissonance has traditionally been treated in pop music. Then we can see what’s changed. (*This is Part 1 of a two-part investigation of the unjazz trend, to read Part 2, please visit Ben Morss’ blog here.)

Traditional Dissonance Treatment in Pop

Generally speaking, modern pop songs resolve dissonances in ways that are reminiscent of classical music. It just tends to be a more casual process, in which dissonances are arrived at more spontaneously and can persist for longer. A typical case is “We Are Young” by fun (feat. Janelle Monáe).

Let’s look at its traditional pop-rock chorus. Omitting some of the fancy vocal melisma, here are the first eight measures:

Audio Player

You’ll notice there’s an emphasis on strongly consonant tones. The first pitch is F, a unison over the F chord. On the word “tonight,” Nate Reuss descends through a F major triad, avoiding any dissonance whatsoever. He then moves through E, a dissonant passing tone, to D over the D minor chord; another strong unison. His voice then rises through F and G to A, another strong interval, a 5th.

Over the Bb chord, the melody uses the highly consonant first and third scale degrees. Then it hits a strong dissonance over the C chord — an A, the 6th scale degree. This wants to resolve down to a G, the 5th degree. Such a resolution would sound too formal, like classical music, so Reuss obscures it in a complex melisma which resolves to G but then quickly drops down to E, a consonant 3rd degree.

So that’s the usual state of things. There’s nothing wrong with it! These powerful intervals make for powerful, stable, anthemic melodies. They just don’t break new ground in dissonance treatment.

Note also that we’re never in doubt about the harmony that’s being expressed in any particular region. In most traditional pop, especially in rock, chords are declared proudly and clearly. It’s part of the language. We may not always be sure what key we’re in, but in almost all cases we know what the current chord is. Just listen, for example, to the verse of All Time Low’s 2020 song with blackbear, “Monsters.” It screams, “I’m in C minor!”

Let’s now look at a couple of interesting ways in which rock and pop have traditionally treated dissonances — ways that were never used in classical music. Then we’ll see how modern R&B and hip-hop have taken these techniques to a new level.

Consonant before, consonant now.

If a pitch is consonant over one chord, it can then be treated as a consonance over a subsequent chord where it would normally be dissonant. These dissonances often sound catchy, as the ear likes to be surprised with tension that resolves.

A corollary of this principle is that a melodic phrase that’s consonant over one chord can be reused over chords where it contains dissonances. The listener’s just heard those dissonances as consonant, or they’re about to. They know that when the original chord comes around again, they’ll be consonant again. It forgives the temporary dissonances! This is a dissonance treatment technique from our list above: consonant once, consonant again.

This technique dates back to the early days of rock ‘n’ roll, when musicians repeated the same melodic phrase over different chords in the 12-bar blues progression, sometimes modifying it slightly to match each chord, sometimes not. No doubt this technique, like so many things in modern American pop music, originates in the blues.

Check out, for example, in 1958, Chuck Berry’s groundbreaking “Johnny B. Goode.”

The chorus starts with this melodic phrase:

Audio Player

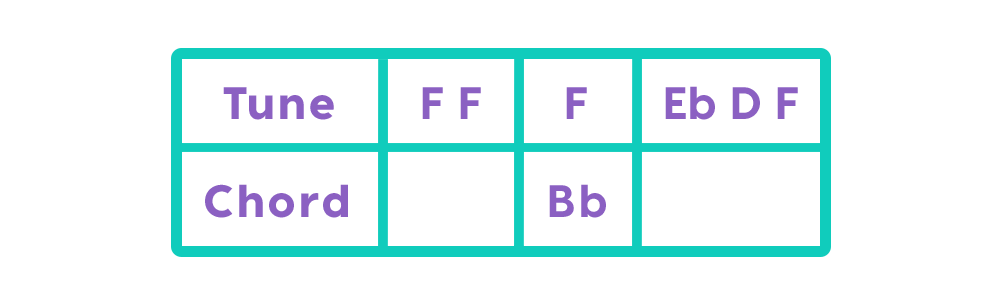

It’s based on a strong, consonant F (the 5th scale degree) that dips down to a consonant D (the 3rd scale degree) before returning home to F. This phrase repeats. Then, the harmony changes to E♭. But the melody doesn’t change, even though the F is now a dissonant 2nd scale degree, and the D is a dissonant 7th:

Audio Player

It’s dissonant, but dissonances are catchy. And we like it when they’re resolved, as happens when the next chord comes around, which is a B♭, and everything’s consonant again.

Fast forward to 1982, when 12-bar blues progressions still made an occasional visit to the pop charts. That year, in the chorus of his hit “Delirious,” Prince repeated a melodic phrase in the keyboard riff and another in the vocals in just this way, consonant over the I chord, dissonant over the IV chord, and consonant at the end.

Like so many other ideas from the blues, this one seeped into the pop. In 1984, in “Born in the USA,” Bruce Springsteen repeated keyboard lines and melodic lines without regard to the underlying chords. In 2000, Blink-182 repeated the same melodic phrase over different chords in “All the Small Things.”

And this technique is still in wide use today. Just listen to Weezer’s 2020 song “Hero.”

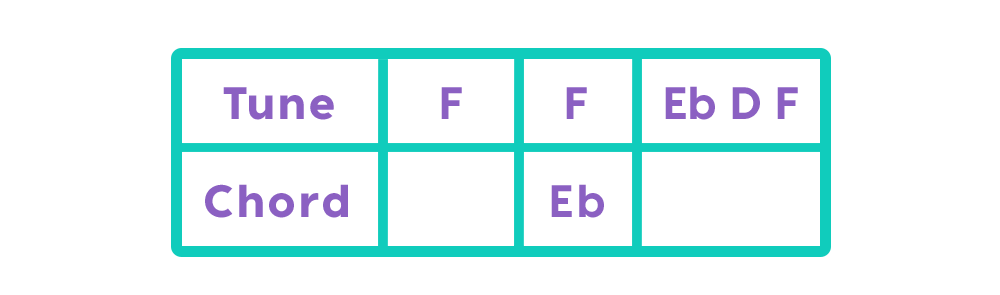

The verse begins with a phrase that goes D-B-A-B over a D chord, where it’s quite consonant, despite the slightly dissonant ending B. Then, that phrase repeats over the next chord, an A/C#. The D is a dissonant fourth over the A. It’s actually a very dissonant minor second over the C# in the bass.

But our ears accept this dissonance, because we’ve just heard it as a consonance, and we expect it to be resolved shortly. Indeed, the next melodic phrase is a consonant B-A-F#-A over a B minor chord.

Our ears would have preferred to hear the D as a consonance, which we do in the final phrase, whose melody rises A-B-C#-D-E, with full chords supporting the last four pitches with the same notes in the bass, before landing back on D over a D chord when the melody repeats. It’s a strong resolution to the first scale degree.

Stick to your scale.

In the olden days, as chords changed, the pitches used over those chords would change to match the chords. Specifically, the pitches over any given chord would be drawn from a scale that matched the chord. There might be a few such scales, of course, and I really need to avoid going into a long digression about how classical composers foreshadowed a modulation through subtle shifts in the scale — but at least you’d try.

Even today, jazz and rock players learn to improvise by learning scales that match chords.

However, in pop and rock, it’s possible to simply use a single scale over a whole set of chords, and then not worry so much about dissonances between the tune and any particular chord. As long as you stay in the scale of the song, you’re golden. This is: stick with your scale.

Third Eye Blind’s 1997 song “Semi-Charmed Life” is a fine example of both stick with your scale and consonant once, consonant again.

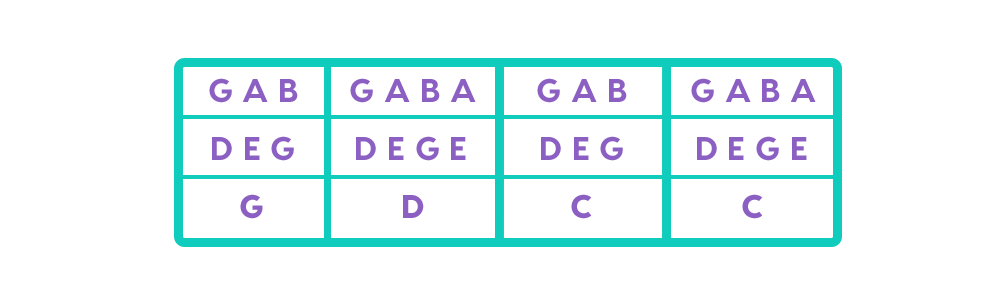

It opens with a melodic phrase that repeats over different chords, in two-part harmony:

Audio Player

Both the top and bottom parts of the first phrase are highly consonant over the first chord, G. Then the same phrase is reused over the subsequent D and C chords, even though in these context many are dissonant. For example, the strong G and E in the second measure are a 4th and 2nd over the D, and the strong D is a dissonant 2nd over the C in the third measure. But they all make sense because they were initially consonant over the G. Otherwise, Stephan Jenkins would never have thought to sing the line D-E-G-E over a D chord. It simply wouldn’t have made sense (consonant once, consonant again).

This section also exhibits stick with your scale. Every pitch sung there is part of the G pentatonic scale (G A B D E). This is also true of the song’s verse, a long, semi-spoken bit drawn from the same scale, which is deployed without regard to the underlying chords.

Stick with your scale may have originated with untrained musicians who didn’t really know what scales were, or that it was possible to switch scales to match a particular chord. Instead, they just found a scale that sort of matched the whole song, and they ran with it. This isn’t really a problem, as many melodies stay within a single scale. This tends to make them more accessible and smoother. However it began, it’s now characteristic of the style, and our ears accept it as normal.

Stick with your scale will be an especially crucial idea when we get into rappers who sing. Don’t forget it!

The consonant 2nd, and beyond.

While most traditional pop and rock songs resolve traditionally dissonant pitches, they don’t always. In particular, it’s not that unusual to treat the 2nd scale degree as a consonance. I’ve written before about an extreme example; Filter’s 1999 song “Take a Picture,” whose chorus consists entirely of 2nds.

It’s not hard to find more cases. Think of the chorus of Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun,” the part where Chris Cornell sings the last word of “wash away the rain.” In fact, listen to the whole song. It’s one long acid hit of melodic dissonance, with even an unresolved tritone. Of course, more experimental rock, such as psychedelic rock, may contain adventuresome dissonances normally rare in the genre.

Still, normally, in pop and rock, everything that isn’t a 1st, 3rd, or 5th scale degree gets resolved eventually. Soon we’ll watch R&B and hip-hop singers chip away at this.

But before we can truly get into the unjazz, let’s briefly look at how jazz harmonies have made a resurgence on the pop charts.

+ Read more on Flypaper: “How D’Angelo Uses Funky Dominant Sevenths in ‘Sugah Daddy’.”

Jazz Harmony in Modern Pop — the Un-Unjazz

When we talk about more complex harmony in pop music, the first thing we’d look for is: are songs featuring chords beyond the major and minor that have dominated much of pop since rock ‘n’ roll burst onto the scene in the mid-1950s? After all, where else is there to go but up — toward 7ths, 9ths, and beyond?

Plenty of the musicians who invented the sounds of 1970s soul and funk knew jazz and incorporated it into their music. This is true in particular of Nile Rodgers, one of the creators of guitar funk playing. Modern Top 40 is intensely influenced both by smooth R&B and by 1970s funk. This has brought lightly jazz-influenced harmonies back into the Top 40.

A few examples:

Dua Lipa – “Levitating”

This song’s progression is Cm7 – Gm7 – Fm7 – Cm7. The 7ths can be heard most clearly when the big keyboard chords enter in the middle of the chorus. Here, the jazz chords emanate from a 1970s funk/disco influence. To learn more about the funky guitar playing in this song, check out this Switched On Pop podcast episode.

Kali Uchis – “telepatía”

This song is based on a chord loop that goes GM7 – B7 – Em9 – A13. This song isn’t really funky; its jazz is more the smooth jazz / quiet storm variety.

Justin Bieber (feat. Daniel Caesar & Giveon) – “Peaches”

Another lush 1970s progression, ready for the supermarket. With its gentle, descending FM7 – Em7 – Dm7 – CM7 progression, it’s music to buy Cheez Whiz to.

Giveon – “Heartbreak Anniversary”

This true R&B throwback (a piano ballad!) is based on a CM7 – E7 – FM7 progression.

We won’t go through the entire Spotify Top 50 playlist. But we can’t leave before we mention Silk Sonic’s recent throwback, “Leave the Door Open,” which is blessed with a 500-gallon hot-tub-ful of sweet 1970s jazz harmony.

Meanwhile, many rap songs incorporate the sound of jazz by simply using samples that include jazz chords. Nothing I could say here would match the eloquence and beauty of this video, in which Robert Glasper declares that “Jazz is the mother of hip-hop.”

Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 album, To Pimp a Butterfly embraces the essence of jazz on a much deeper level, not just in using a variety of jazz styles dating back to bebop, but also with its jazz-like complex textures, bits of sound collage, and arrangements that mix textures in ways that sound spontaneous and are far more granular and less regular than verses and choruses. And let us not forget the jazz-influenced rap groups of the late ’80s and early ’90s, like Digable Planets and A Tribe Called Quest.

I love that I can now turn on a Top 40 station and bathe my ears in such harmonic richness. True, most songs are still limited to a single chord progression, but at least those chords aren’t just majors and minors. But these songs don’t exhibit unjazz, the innovative dissonance treatment and melodic approach I keep telling you this article is about. Now we’re ready for that. Let’s dive in!

And remember, we’re super excited to launch our forthcoming course with jazz pianist and beat producer, Kiefer. So if jazzy hip-hop excites you as much as it does us, you need to sign up for Soundfly’s newsletter to be informed as soon as it’s live!

The Birth of the Unjazz

TLC – “No Scrubs”

When hip-hop first seeped into the world of R&B, some R&B artists embarked on new adventures in harmonic dissonance. This could be heard occasionally as far back as 1999, when TLC released “No Scrubs.” It’s an early example of treating elevated scale degrees as consonances, stick with your scale, and climbing down ☰ the ladder of thirds.

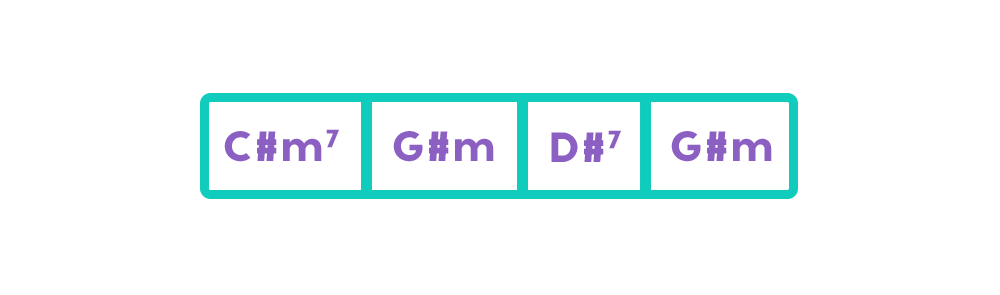

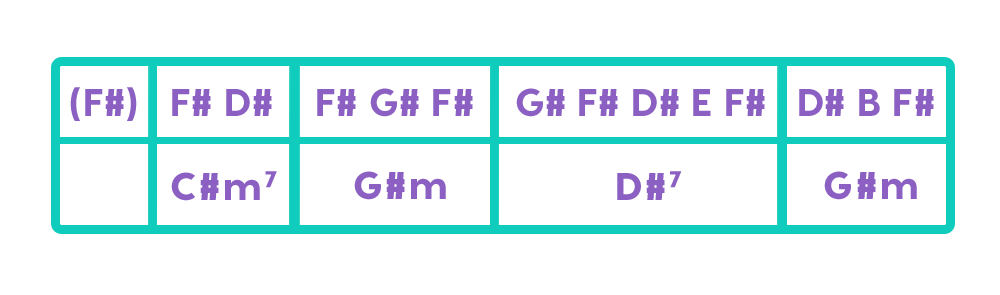

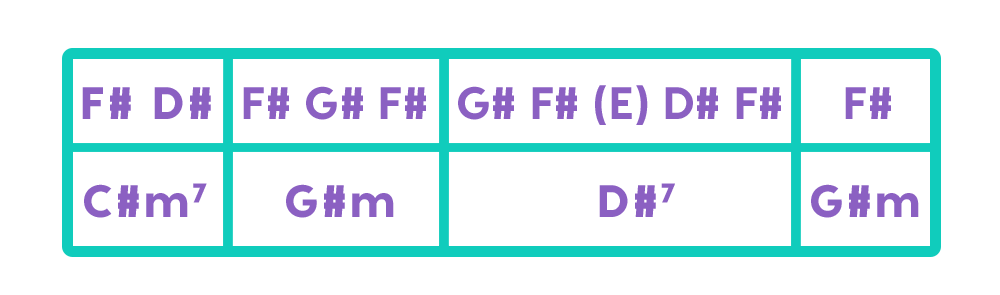

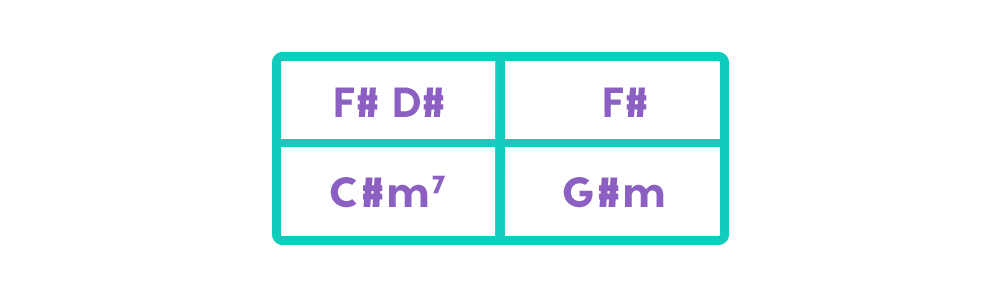

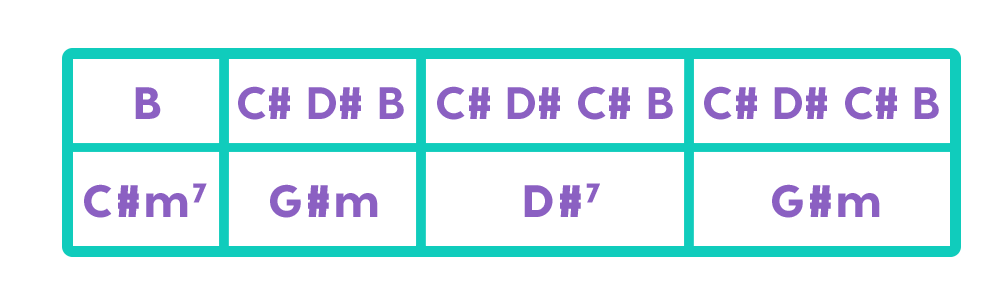

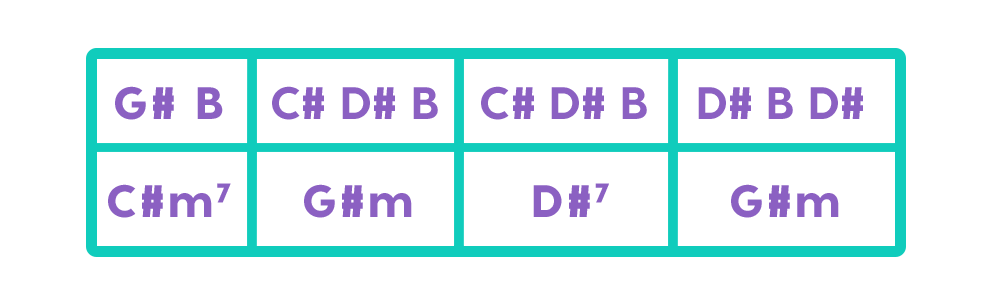

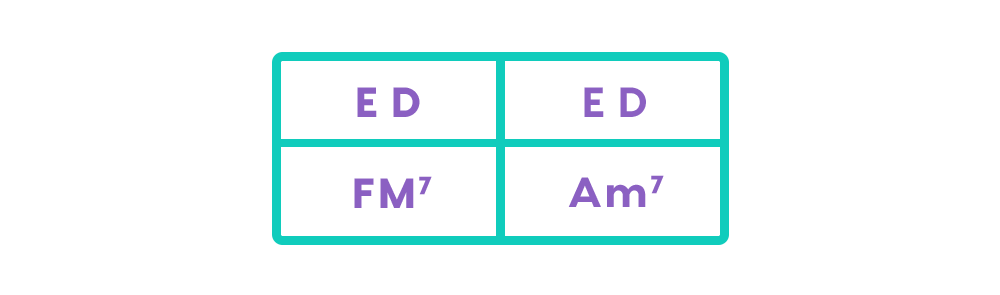

“No Scrubs” is based on the following chord progression, which is used throughout with the exception of a contrasting bridge:

Audio Player

This progression consists of two cadences to G# minor — a iv-i plagal cadence and a very traditional V7-I cadence. These make “No Scrubs” sit firmly in the key of G# minor. The melody uses the G# minor scale throughout, though the A# is saved for the bridge. (In pop music, the second scale degree is sometimes strategically reserved and then deployed at a key moment.)

Let’s start with the verse.

Audio Player

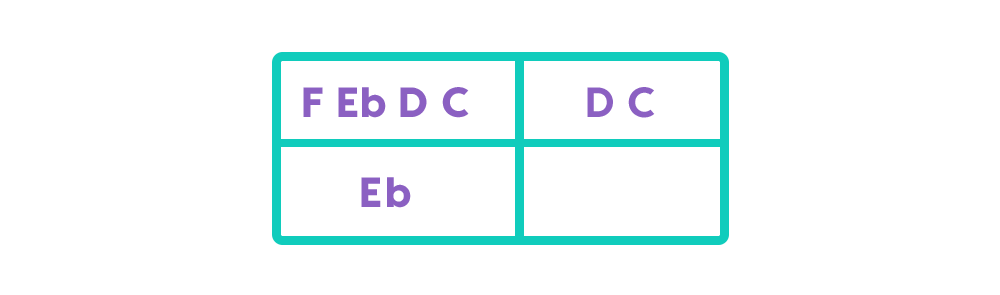

Skipping the pickup note, the first three pitches of the verse are quite striking. Let’s focus on them:

Audio Player

It’s not common to start a tune on the 11th scale degree, but that’s just what the F# is. We’d expect this to resolve, presumably down to E. Instead, it jumps one rung down the ladder of thirds to D#, the 9th. Now we’d figure the D# would resolve, maybe back to the E we just skipped. Instead, the tune leaps all the way down to a low F#, a 7th over the G#m, another rung down the ladder of thirds. This low 7th is relatively stable; effectively, the dissonant 11th has resolved by being held until the change to G#m made it relatively consonant.

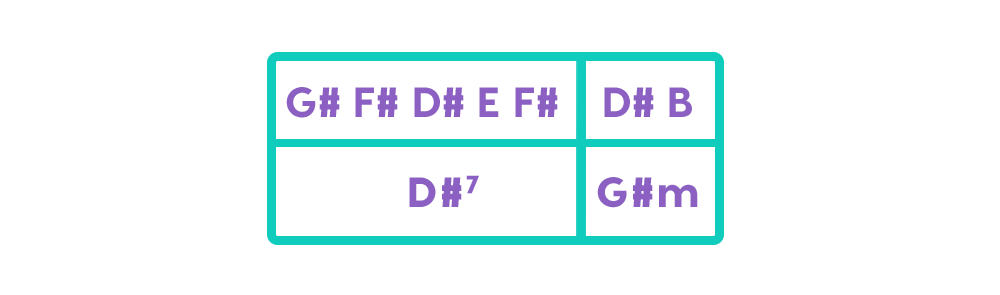

You’d think that the tune would then take a break from dissonance. Instead, it does this:

Audio Player

Yes, it leaps up a ninth from that low F# to a G#, the verse’s high point. That G# is another 11th , and it’s even more dissonant than the F# was over the C#m chord, since it occurs over a D# major triad that contains a clashing F-double-sharp. Fortunately, our tortured ears are now treated to the first traditional dissonance resolution, as the G# resolves down to an F#. Of course, that F# does still clash horribly with the F-double-sharp in the chord. Ultimately we descend the ladder of thirds from F# through D# to rest on B, a nice consonant third over the G#m chord.

How can all these dissonant tones exist over the D# chord?

It’s the principle of stick with your scale. As long as the melody consistently uses the G# minor scale, our ear can ignore dissonances that result from these tones being used over chords where they clash. It also helps that the only instrument that expresses the full chords is the synth harpsichord-like sound, which is mixed quietly, drowned out completely by drums, bass, and vocals. We hear the G# as an expressive upper neighbor to a consonant third, and the F# can be heard as a bluesy minor third.

This verse is all about descending from F# through D# down to B, down the ☰ ladder of thirds. In the G# minor tonality, that’s an unsurprising descent from 7th scale degree to 5th to 3rd. It’s unusual that we don’t hear much of the notes between those – the E or C#. And it’s a lot more unusual that the F# and D# are introduced to us over the C# chord, where they’re an 11th and 9th. And, again, the emphasis on the twin 11ths of the F# and the G#.

The chorus lies further down the ☰ ladder of thirds, emphasizing 7ths, 5ths, and 3rds, hovering around the lower pitches of D# and B and a strongly emphasized passing C#. Despite the occasional emphasized 9th or 11th, it represents a point of relative resolution.

Audio Player

“Day ‘n’ Nite”

In the years since “No Scrubs,” hip-hop and R&B have worked together to expand what we regard as melodically consonant. Let’s look first at singing rappers. Then, we’ll look at R&B singers who are influenced by hip-hop. In between, we’ll look at “Work,” a song where we’ll find both!

Rappers have sung on and off since the beginnings of hip-hop. Sometimes, they did a bit of both, rapping in repetitive melodic cells. But this rap-singing truly became a thing at the end of the 2000s, when Kid Cudi and Dot Da Genius released “Day ‘n’ Nite”. This hypnotic, compelling song is a fine case of harmonic ambiguity and an introduction to root in the voice.

Harmonic ambiguity isn’t new in hip-hop. The style has long contained a huge variety of backing instrumentals, including some with little harmonic content. What’s new here is that Dot Da Genius and Kid Cudi created an ambiguous, trippy track — and realized it would serve the song’s purpose to sing over it.

For the first 40 seconds, this backing track consists of simple drums and a hypnotic repeated synth line:

Audio Player

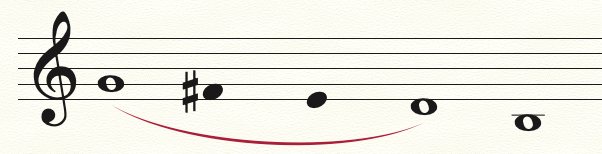

By itself, this synth line doesn’t create a clear sense of a specific harmony. To me, it sounds most like an elaboration of a G major chord in first inversion:

But this tune could also imply E minor, B minor, G major, or some succession of these chords. The tonality is simply ambiguous until Kid Cudi sings. When he does sing, it’s quite unusual: he repeats the same short, hypnotic melody throughout the song. Here’s how it starts:

Audio Player

Placing the vocal melody against the melodic riff, you hear this:

Audio Player

The track has no bass until the 1:50 mark. Until then, Cudi’s voice is the only bass we have: root in the voice. This was quite unusual at the time, but we’ll soon see it frequently in the music of Drake. The voice can define the bass of a chord. It tends to do so weakly. Modern AutoTune and other effects help, but the weak bass helps create harmonic ambiguity.

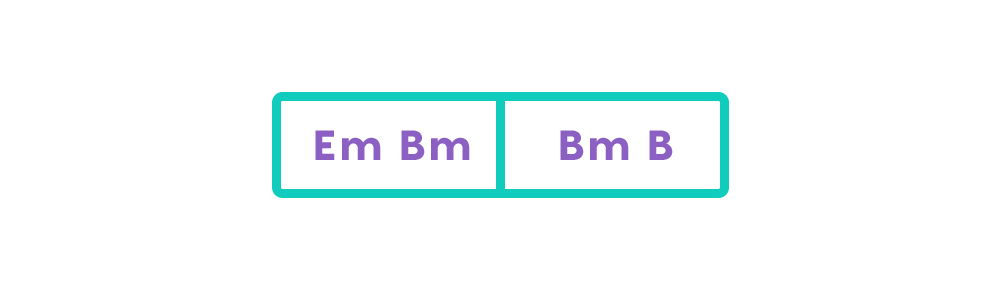

In any case, Cudi’s voice weakly defines the first chord as E minor. There’s no 5th — just the 1st and 3rd scale degrees. Adding to the ambiguity , of the three notes that Cudi sings in that first measure, two are a half-step away from the synth.

With the addition of the vocals, the second measure is now clearly a B minor. In the third measure, Cudi ends the phrase with a D on the third beat, which matches the synth but does little to strengthen the vague E minor tonality. In the seventh measure, he throws a D on the final eighth note, sitting all by itself. Again this matches the synth, but it’s quite striking, ending the tune on a dissonance that would almost be impossible to sing with confidence without AutoTune.

This eight-measure phrase happens twice. Just when we think we might understand these chords, at 0:40 of the track, a lush synth enters, playing chords that aren’t quite what we expected:

Audio Player

Yes, the pattern goes to the B minor two beats early, and it includes a B major. The chords still mostly match the vocal melody, but the D# in the B major chord clashes with the D in the synth. It’s a strange, psychedelic, and beautiful effect. And the strong V-I cadence in this forest of ambiguity is a welcome release, producing a wonderful climax that reminds me of the coda of Prince’s “When Doves Cry.”

I think this harmonic ambiguity is absolutely key to the song’s success. It’s what makes a repetitive song bear repeated listenings. It keeps surprising the ear; you keep wanting to figure out what’s going on. (You should also watch this fantastic interview where Dot Da Genius explains how he created the track, although he says not a word about the trippy harmonic content or daringly minimalistic aesthetic.)

When Kanye West heard “Day ‘n’ Nite”, he invited Kid Cudi to collaborate on a sung album of his own, 808s and Heartbreak. This record, while groundbreaking for other reasons, doesn’t include the harmonic ambiguity and novel dissonance treatment we’re calling “unjazz.” But the record did influence an aspiring rapper who would soon not only change hip-hop by inventing a new style of rap singing, but who would blaze new trails in melodic dissonance and harmonic ambiguity. Can you guess who? (Hint: his rapper name rhymes with “Heartbreak.”)

Enter Drake.

By creating a style in which he sings repetitive phrases in a way that’s part melody, part sing-song rap, Drake has redefined the role and range of the rapper. Indeed, building on “Day ‘N’ Nite” and 808s and Heartbreak, Drake doesn’t always sing a melody of the sort we’re used to. It’s sort of like rap, but on pitches, using melodic cells that repeat, develop, and adapt to the words.

Many traditional pop melodies progress toward goals. Verses lead via pre-choruses to climactic choruses — for example, in Katy Perry and Ester Dean’s song “Firework,” Drake isn’t really interested in goal-directed melodies or carving out contrasting spaces for verses and choruses. He’s simply more interested in exploring and prolonging a set of pitches as he works his way through introspective song topics. His approach will influence the rest of the music we’ll look at in this article.

In early songs like “Houstatlantavegas” and “Best I Ever Had,” Drake writes melodies that are catchy and likeable, but not particularly harmonically adventurous. As his career progresses, though, he starts to explore areas that previous singing rappers would never have considered. Let’s look at two examples from his 2013 album Nothing Was the Same: “Furthest Thing” and “Started from the Bottom.”

Drake – “Furthest Thing”

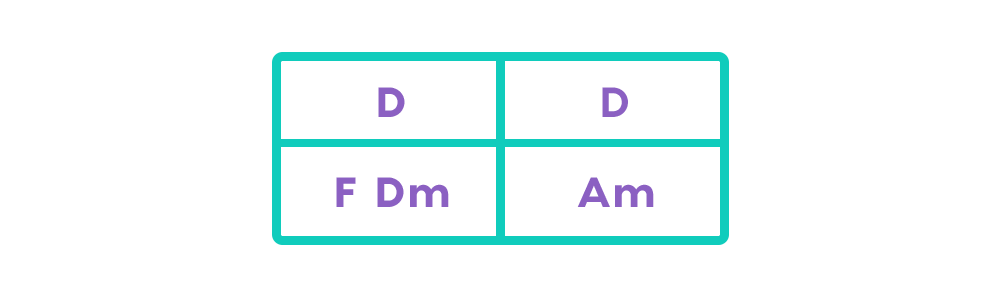

The song’s instrumental track is based on a piano and synths drenched in effects that make them distant and diffuse. The instruments define a repeating F major 7th chord and A minor 7th. Here’s a very simplified version:

Audio Player

When Drake’s voice first enters at 0:14, there’s no bass, making his voice the lowest thing we hear clearly. He intones lyrics in phrases that descend E – D:

Audio Player

Normally, we’d expect this D to resolve down to a consonant C. But it doesn’t. Over the F chord, the D is an unresolved 6th, and over the A chord, it’s a particularly unusual unresolved 4th.

At 0:28, as the melody intensifies and adds notes, Drake incorporates an upper neighbor, F, into his tune. Over an F chord, normally F would be the consonant tone to which the E would resolve. Here, though, it doesn’t feel that way. The F always lies between two E’s, like a dissonant neighbor tone to the E, making the E play the novel role of a consonant 7th.

Audio Player

That’s strange! But, do you remember “No Scrubs?” We heard consonant 7ths there as well. Such 7ths aren’t unusual in more adventurous R&B, or even in blues-influenced rock, where 7th chords are the norm and the 7th is a strong melodic pitch. It’s elevated scale degrees.

Note that, in the fourth measure of this melodic phrase, Drake does finally resolve the D down to a C, a conventionally consonant 5th scale degree. This resolution is just delayed for a mind-bending 20 seconds. At 0:55, the chorus doubles down on the idea of a consonant 4th scale degree. In the first two measures, Drake sings only the note D:

Audio Player

In the next two measures, his melody expands both up and down from the D, with what is ultimately another delayed resolution of the D down to C — this time, from a 4th to a 3rd scale degree. After singing the C, he drops down briefly to an A, the root of the chord, the most consonant tone of all. But then, in the final measure, he returns to the D, and stays there, never to resolve it.

For Drake, this 4th scale degree is absolutely a consonance.

Audio Player

A consonant 4th scale degree. What’s happening here?

It’s simply our first example of normalizing dissonant pitches as consonant . Maybe Drake was thinking about a jazz-inflected Am11 chord when he sang that D. Most likely that chord was merely a vague idea in his mind — but he knew that this note, one step away from a traditional consonance, would introduce a jazzy flavor. Even though the chord in the instrumental is a plain old A minor, there’s enough jazz in the track to inspire a singer with sensitive ears to add some more. It takes courage for a singer to sing such a dissonant note, but, as noted above, it helps to know you can use effects like AutoTune to strengthen your voice.

In any case, this sound — the sound of a pitch that’s a step away from resolution and remains so — will become characteristic of Drake’s melodic style.

Drake – “Started From the Bottom”

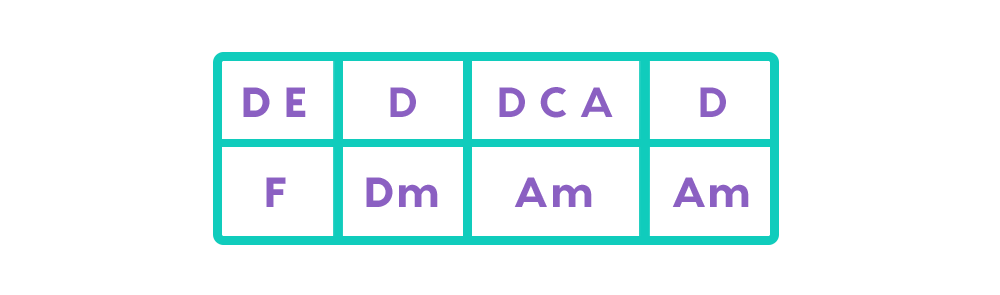

This song is built on another diffuse, ambient sample. This one mixes piano, synth, and maybe some mellow guitar. Generally, the instrumental prolongs an E♭ chord with a melodic resolution from A-natural to G. A simplified version:

Audio Player

After the song’s introduction, Mike Zombie, the producer, adds in a minimal amount of bass. The kick drum might include a bit of 808 bass moved down to an E♭. I can’t tell. Soon a swooping bass enters that avoids strongly defined pitches. So the song’s E♭ tonality is defined quite loosely. It’s an example of harmonic ambiguity.

Drake performs most of this song in a sing-song style that’s part rapped, part pitched, which reminds my legit-music brain of the atonal classical composer Arnold Schoenberg’s “Sprechstimme.”

He hues closely to a pitch that’s sometimes A, sometimes B♭, sometimes nestled between. Generally I’d say he’s closer to the A. And that’s where he stays throughout the song. Yes, that’s right — he’s singing the tritone, one of the most dissonant intervals known to humankind — what the ancients called diablous in musica. I’ve never heard anything else like it.

Why does Drake focus on this odd pitch? It’s not an easy one to sing. No doubt it’s inspired by the prominent A at the start of the sample. But it’s also another example where Drake hones in on a dissonant pitch that’s a scale degree away from a consonance . His musical ear is strong enough to let him focus on this pitch and make it melodic.

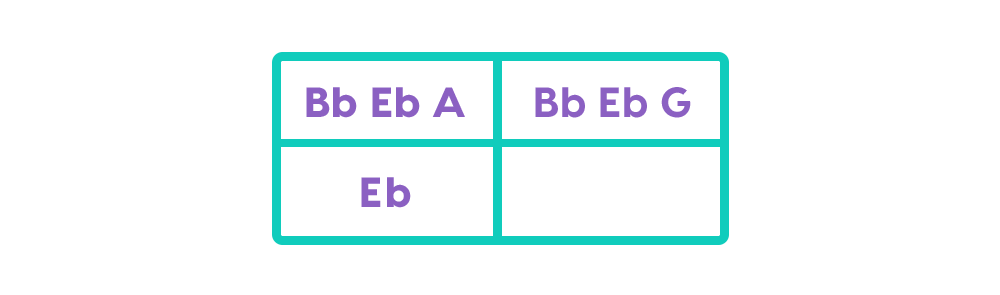

At 1:51, the drums vanish and Drake introduces a contrasting section; a sort of bridge. One might think he’d seize this opportunity to resolve the dissonance. Instead, he doubles down on dissonance, singing a new melody that descends seven times from F to C. For example:

Audio Player

It’s a nice melody that’s in a nice, traditional scale. It would even fit in the key of E♭. But it descends from the 9th scale degree to the 6th. Once again, the whole thing feels like it’s off by a single step. You could “fix” it by placing it over a F instead of an E♭:

Audio Player

But then it would sound like a conventional pop song. It would completely lose that off-kilter, jazz-like, soul-like dissonance! It would be too consonant, more conventional, more boring. Instead, he helps to pioneer the technique of singing in the wrong scale.

The eighth time he sings the melody, in order to return to the main song, he ends higher, simply descending F – E♭ – D. Yes, he ends on the major 7th, another utter dissonance. But by now, he’s normalized this dissonant pitch as a consonance.

The coolest thing of all is that this song, for all of its harmonic quirkiness — or perhaps because of it — was a top 10 hit in the U.S.

Although these ways of treating dissonance originate in jazz, to me, this music sounds little like jazz. There’s no swing, no jazzy rhythms. The instruments aren’t improvising. The chords connect to jazz only tentatively. On the other hand, the vocal approach has a lot to do with jazz as we’ve known it since bebop — the idea of an instrument playing lots of notes, playing virtuosically with melodic and rhythmic ideas before reverting to a traditionally singable tune in a chorus.

Its roots lies in jazz. But it’s not jazz. Thus, we call it “unjazz!”

This was Part 1 of a two-part investigation of the unjazz trend, to read Part 2, please visit Ben Morss’ blog here.

Ben Morss earned a BA in Computer Science from Harvard and a PhD in Music at UC Davis, which he immediately squandered by playing with bands like Cake, Wheatus, and Onward Chariots. An alumnus of the BMI Musical Theater Workshop, Ben co-wrote two musicals based on Angelina Ballerina, and he’s currently working on a musical/opera that’s not really about Steve Jobs.

Music Research,

Music Research,  Songwriting tagged

Songwriting tagged  jazz,

jazz,  music theory,

music theory,  pop

pop

Reader Comments